A REFLECTION ON TRAUMA, TRAUMATIZATION, TRAUMA-INFORMED, AND RECOVERY - PATRICK TOMLINSON (2023)

Date added: 08/09/23

Download a Free PDF of this Article

The full version of this article and the Chapter - Trauma-Informed Practice can be downloaded at the bottom of this page

Introduction

Recently I was asked if I could write a short explanation of what a trauma-informed approach to healing and growth might look like. This got me reflecting on the subject and led to this article.

I have been involved with therapeutic services for children and young people who have suffered trauma and other adversities since 1983. Ten years ago, in 2012, a book I co-authored with Susan Barton, and Rudy Gonzalez, from the Lighthouse Foundation in Melbourne, Australia, was published - Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Young People: An Attachment and Trauma-Informed Model for Practice. We included the word attachment in the title of the book as we believe that a relational approach is vital. As Farragher and Yanosy (2005, p.100) stated,

I have been involved with therapeutic services for children and young people who have suffered trauma and other adversities since 1983. Ten years ago, in 2012, a book I co-authored with Susan Barton, and Rudy Gonzalez, from the Lighthouse Foundation in Melbourne, Australia, was published - Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Young People: An Attachment and Trauma-Informed Model for Practice. We included the word attachment in the title of the book as we believe that a relational approach is vital. As Farragher and Yanosy (2005, p.100) stated,

"Recovery from injuries perpetrated in a social context must occur in a social context."

Our book was about complex childhood trauma, and its impact on development, therapeutic work, and recovery. Complex trauma is sometimes referred to as developmental trauma (Van der Kolk, 2005). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) explain,

Complex trauma describes both children’s exposure to multiple traumatic events—often of an invasive, interpersonal nature—and the wide-ranging, long-term effects of this exposure. These events are severe and pervasive, such as abuse or profound neglect. They usually occur early in life and can disrupt many aspects of the child’s development and the formation of a sense of self. Since these events often occur with a caregiver, they interfere with the child’s ability to form a secure attachment. Many aspects of a child’s healthy physical and mental development rely on this primary source of safety and stability.

Thinking of what we wrote in 2012 has focused my attention on what has happened in the world at large in thinking about trauma, as well as how my thoughts have evolved. I hope this article captures and affirms some of the enduring and emerging perspectives.

Definitions of trauma

Menschner and Maul (2016, p.2) argue that there is no Universal definition of trauma and state,

Experts tend to create their own definition of trauma based on their clinical experiences. However, the most commonly referenced definition is from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA),

“Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”

While Menschner and Maul are correct that there may be variations on the theme of what trauma means, I think that since the late 19th century, the definition has been consistent. The interpretation of what trauma means and how it is used has been less consistent and sometimes confused. Trauma has been defined in the world of psychology for well over 100 years. But as it is an inevitable part of human nature it has been known about and understood to different degrees for 1000s of years. For example, some of the wisdom of ancient tribal life is recognized to contain vital aspects of trauma recovery, such as movement and rhythm, and predictable rituals. It is important to recognize that as well as science, our knowledge comes from our experience of life, from experiences shared with others we meet or hear about, and from what is written. Pynoos et al. (2007, p.332) in the book Traumatic Stress capture this well,

"From the earliest account of an adolescent’s experience of a catastrophic disaster, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in the Letters of Pliny the Younger (100—113A.D./1931); through the autobiographical description of intrafamilial abuse and societal violence provided by Maxim Gorky in My Childhood (1913/1965); to the powerful literary rendering of the Holocaust by Elie Wiesel in Night (1958/1960) and the trenchant autobiographical account of childhood rape by Maya Angelou in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), authors have reflected on the formative influences of traumatic experiences in childhood. Indeed, it is a common assumption that personal creativity and character are often born out of early tragedy."

"From the earliest account of an adolescent’s experience of a catastrophic disaster, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in the Letters of Pliny the Younger (100—113A.D./1931); through the autobiographical description of intrafamilial abuse and societal violence provided by Maxim Gorky in My Childhood (1913/1965); to the powerful literary rendering of the Holocaust by Elie Wiesel in Night (1958/1960) and the trenchant autobiographical account of childhood rape by Maya Angelou in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), authors have reflected on the formative influences of traumatic experiences in childhood. Indeed, it is a common assumption that personal creativity and character are often born out of early tragedy."

One of the first psychological definitions of trauma was by Freud and Breuer in 1893,

"Psychological trauma or more precisely the memory of the trauma – acts like a foreign body which long after its entry must continue to be regarded as the agent that still is at work."

In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), Freud explains that the disturbance arises when the ego is totally unprepared for a traumatizing event of an external kind. Later (1926, in Pynoos et al. 2007, p.338) he defined a traumatic situation as one,

… in which the subject is helpless, external and internal dangers, real dangers and instinctual demands converge. Whether the ego is suffering from a pain which will not stop or experiencing an accumulation of instinctual needs which cannot obtain satisfaction, the economic situation is the same, and the motor helplessness of the ego finds expression in psychical helplessness.

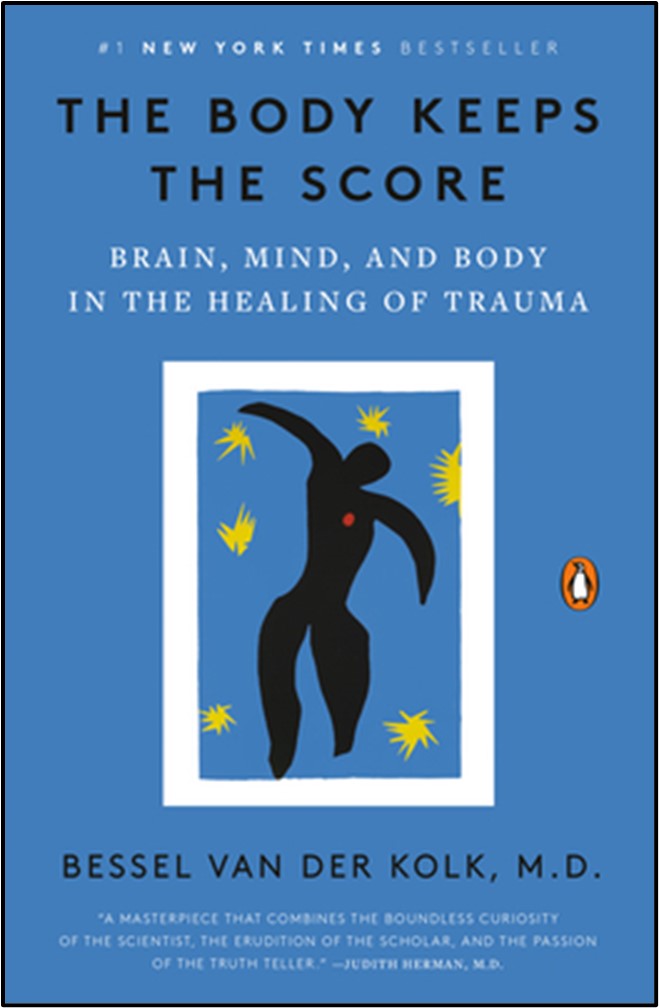

When a traumatic experience cannot be integrated, as Freud explained and Bessel van der Kolk (2014) says, ‘the body keeps the score’. Unintegrated trauma is felt in the body. Interestingly, Van der Kolk is one of the present-day neuroscientists who writes about the long tradition of neuroscience, dating back to Freud and others such as the French Psychologist Pierre Janet.

Van der Kolk (2021) summarizes some key points about trauma,

The most important thing to know is that there's a difference between trauma and stress... The problem with trauma is that when it's over, your body continues to relive it… So, unlike what we first thought, trauma is actually extremely common… There's a lot of debates of what the trauma is to this day. But basically, trauma is something that happens to you that makes you so upset that it overwhelms you. And there is nothing you can do to stave off the inevitable… But the trauma is not the event that happens, the trauma is how you respond to it.

One of the key points that Van der Kolk makes is that trauma, post-Vietnam war became associated mainly with violent events, such as those experienced in combat. Interestingly, this more literal understanding which defined Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is narrower than Freud’s earlier explanation. Freud paid attention to a person’s internal and not only external world. It was believed that trauma could also be caused by significant but not so visibly violent events and that the internal world is as significant as the external. Whatever the cause of trauma, Van der Kolk and Newman (2007, p.7) state its impact,

The posttraumatic syndrome is the result of a failure of time to heal all wounds. The memory of the trauma is not integrated and accepted as a part of one’s personal past.

In a review of Van der Kolk’s book The Body Keeps the Score, Forte (2019) says the book establishes early on that,

Trauma is an almost universal part of the human experience.

Forte outlines the key points made in the book about the impact of trauma,

• Flashbacks and projection

• The othering of self and others

• Disembodiment

• Panic attacks

• Chronically elevated stress hormones

• Overcontrol and hypervigilance

• Dissociation and avoidance

• Difficulty integrating traumatic memories

• Sensory overload

• Addiction to trauma

I think one of the reasons so many people are interested in trauma is because we can all identify with it and will most likely have remnants of trauma we need to work through. Most of us can probably say we have experienced some of the above. To do so is a part of ordinary life, it is only a serious problem when we get stuck with these symptoms in a manner that is disabling.

Sinason (2022, p.116) also observed that,

George Santayana the Spanish American Philosopher (1863-1952) put this in clear terms for all (1905, p.284): “Those who cannot remember the past are deemed to repeat it.”

The psychoanalyst Adam Phillips (2002, pp.146-147) talks about how one effect of trauma can be to continuously bring the past into the present so that nothing new is possible.

Trauma is when the past is too present; when, unbeknownst to oneself the past obliterates the present. It is the traumatised person – all of us, to some extent – who says that there is nothing new under the sun; that nothing ever changes. It is the art of art to make the past bearably present so that we can see the future through it. The problem, in other words, is not in making the past present, but in making the past into history.

Continuing the focus on the power of events which may not appear dramatic, the child psychiatrist and paediatrician, Donald Winnicott drew attention to how, in infancy, trauma can be the result of emotional impingement. This is very different to the idea of trauma as an act of violence. In his paper, Morals and Education (1963, p.97), he wrote,

At this early stage the infant does not register what is good or adaptive, but reacts to, and therefore knows about and registers each failure of reliability. Reacting to unreliability in the infant-care process constitutes a trauma, each reaction being an interruption of the infant’s ‘going-on-being’ and a rupture of the infant’s self.

Trauma during infancy may not be noticed except by the infant, who in health will alert the caregivers, by crying for example, who then also notices and responds caringly. However, if the trauma is too severe and frequent, such as in severe neglect, the infant may give up alerting others who never come to meet his/her needs. Winnicott (1956, p.303) explains the consequences of impingement and the infant’s reaction to it,

"lf the mother provides a good enough adaptation to need, the infant’s own line of life is disturbed very little by reactions to impingement. (Naturally, it is the reactions to impingement that count, not the impingements themselves.)… An excess of this reacting produces not frustration but a threat of annihilation. This in my view is a very real primitive anxiety, long antedating any anxiety that includes the word death in its description."

by reactions to impingement. (Naturally, it is the reactions to impingement that count, not the impingements themselves.)… An excess of this reacting produces not frustration but a threat of annihilation. This in my view is a very real primitive anxiety, long antedating any anxiety that includes the word death in its description."

This is a critical point in helping us understand that to feel terror and helplessness, does not only include physically dangerous situations. Winnicott says the infant is continuously on the brink of unthinkable anxiety. Unthinkable anxiety is temporarily impossible to integrate as an experience – it is traumatic. However, in good-enough circumstances, a caregiver(s) can think about the anxiety. This gives the infant an experience of something seemingly unthinkable being managed without further consequence. What was unthinkable increasingly becomes thinkable and integrated. The moments of trauma are recovered from and contribute to the development of the infant and caregiver(s). The infant does not become traumatized. Winnicott (1962, p.57-58) explains,

At the stage which is being discussed it is necessary not to think of the baby as a person who gets hungry, and whose instinctual drives may be met or frustrated, but to think of the baby as an immature being who is all the time on the brink of unthinkable anxiety. Unthinkable anxiety is kept away by this vitally important function of the mother at this stage, her capacity to put herself in the baby’s place and to know what the baby needs in the general management of the body, and therefore of the person. Love, at this stage, can only be shown in terms of body-care, as in the last stage before full-term birth.

Unthinkable anxiety has only a few varieties, each being the clue to one aspect of normal growth.

(1) Going to pieces.

(2) Falling for ever.

(3) Having no relationship to the body.

(4) Having no orientation.

These anxieties which are part of development during infancy are what we commonly associate with trauma. The same process with childhood trauma follows in other situations, where trauma is contained by attunement and thoughtfulness. Where there is not an attuned, containing other in the environment, trauma is more likely to lead to traumatization. This is especially so where the infant, child, or adult does not have the internal resources to provide a sufficiently containing function. If the containing function is missing, which is equally the case in withdrawn and reactive caregivers the result can be traumatic. Referring to the work of the Harvard attachment researcher, Karlen Lyons-Ruth (2003), Van der Kolk (2014, p.120) says,

Karlen and her colleagues had expected that hostile/intrusive behavior on the part of the mothers would be the most powerful predictor of mental instability in their adult children, but they discovered otherwise. Emotional withdrawal had the most profound and long-lasting impact. Emotional distance and role reversal (in which mothers expected the kids to look after them) were specifically linked to aggressive behavior against self and others in the young adults.

Lyons-Ruth’s research looked at the development from infancy to adulthood over 18 years. Her findings suggest that for the infant the experience of impingement through a primary caregiver’s emotional withdrawal can have a more serious traumatic impact on development than the more visibly apparent event of physical abuse, for example.

Unthinkable anxiety is as good a definition of trauma as can be made in two words. It is only when unthinkable anxiety/trauma finds no containment and is repeated that traumatization occurs, and the person may live in a state of continual panic and fear. Dockar-Drysdale (1990, p.122) explains,

I found myself considering the problems of a small boy assaulted by a violent adult. Of course, after the first occasion, such a child would feel acute anxiety and dread that the experience might be repeated. However, when such a trauma occurred constantly, this anxiety would change into severe panic states, such as we have seen in our experiences.

The same unthinkable anxiety may also occur due to the repeated lack of responsiveness to the primary needs of an infant. Freud, S. (1926, p.166) in his paper, Inhibitions Symptoms and Anxiety, made the connection between danger and helplessness and how trauma is experienced when the two are combined. He refers to this sequence as – “anxiety – danger - helplessness (trauma)”. It is the addition of helplessness in a danger situation that makes the situation traumatic. And as he (p.167) says helplessness is especially part of early childhood,

… the period of life which is characterized by motor and psychical helplessness.

While we may easily associate trauma with danger and physical helplessness, psychic dangers and psychic helplessness can also be traumatic. For example, excessive fear of loss due to the unresponsiveness of the primary caregiver. Once trauma has happened, dangers in the future may be responded to with anxiety as a signal that may help anticipate and prevent further trauma. Or when the danger is strongly associated with helplessness the situation may be perceived as if it is already a trauma waiting to happen. The two alternative responses are the difference between passivity and mastery.

Judith Herman (1992, p.33) in her classic book Trauma and Recovery gives her definition of trauma, which  also emphasizes helplessness/powerlessness,

also emphasizes helplessness/powerlessness,

"Psychological trauma is an affliction of the powerless. At the moment of trauma, the victim is rendered helpless by overwhelming force... Traumatic events overwhelm the ordinary systems of care that give people a sense of control, connection and meaning."

Similarly, Bruce Perry (2003, p.17) states,

"Trauma: A psychologically distressing event that is outside the range of usual human experience, often involving a sense of intense fear, terror and helplessness."

Ungar and Perry (2012) also say,

Traumatic stress occurs when an extreme experience overwhelms and alters the individual’s stress-related physiological systems in a way that results in functional compromise.

Levine and Kline’s (2006) statement succinctly summarizes,

Trauma is in the nervous system – not in the event.

This means that what is ultimately traumatic is a person’s reaction to an event and inability to integrate it as an experience. While this is true, I also think that we need to acknowledge that extreme events are nearly always likely to be traumatizing. The questions that are not so clear are how long the person is likely to stay traumatized and what is needed for recovery. Not recovering from a traumatized state is when a person may be diagnosed with PTSD. To meet the criteria for PTSD, symptoms must last longer than one month, and they must be severe enough to interfere with important aspects of daily life.

James (1994, pp.10-11) makes an important point about how the meaning one attaches to an event can be as important as the event itself in determining whether one experiences trauma,

Psychological trauma occurs when an actual or perceived threat of danger overwhelms a person’s usual coping ability. Many situations that are generally highly stressful to children might not be traumatizing to a particular child; some can cope and, even if the situation is repeated or chronic, are not developmentally challenged. The diagnosis of traumatization should be based on the context and meaning of the child’s experience, not just on the event alone. What may appear to be a relatively benign experience from an adult perspective – such as a child getting ‘lost’ for several hours during a family outing – can be traumatizing to a youngster. Conversely, a child held hostage with her family at gunpoint might not comprehend the danger and feel relatively safe.

Valerie Sinason (2020, p.135-136) offers this helpful perspective on the complexity of trauma.

"There is a trauma.

It includes a suddenness of attack that cannot be prepared for, that is intentional or perceived as such; the proximity and severity of the attack matter and it must be outside normal experience and involve a fear of dying.

and severity of the attack matter and it must be outside normal experience and involve a fear of dying.

When it happens, it obviously leads to internal consequences as our psyches have to react.

The impact includes biological and neurological change, terror, shame, loss of love or perceived loss, annihilation anxiety and fear, unconscious guilt, breakdown of a sense of a just world, helplessness and hypervigilance.

These processes are ameliorated or exacerbated by:

Nature of attachment, age, previous history of trauma, protective features in the environment and resilience of the self.

Further danger after the trauma

This includes re-traumatisation, which can occur at the moment there is cognitive awareness of the trauma, past or present; a loving relationship can activate terror of unbearable loss. There can be sexualising of fear, terror, excessive control or risk taking; all the defences needed to survive: delinquency or violent re-enactment, mental illness, phobias, somatisation, addiction. Each new stage of life reawakens old triggers, right through to old age."

The need for creativity and hope

Given this long and consistent history of understanding trauma in the fields of psychology and psychotherapy, it is interesting that Judith Herman titles the first chapter of Trauma and Recovery – “Forgotten History”. She (1992, p.7) states,

The study of psychological trauma has a curious history – one of episodic amnesia. Periods of active investigation have alternated with periods of oblivion. Repeatedly in the past century, similar lines of enquiry have been taken up and abruptly abandoned only to be rediscovered much later. Classic documents of fifty or one hundred years ago often read like contemporary works. Though the field has in fact an abundant and rich tradition, it has been periodically forgotten and must be periodically reclaimed.

The phrase ‘no need to reinvent the wheel’ is often used to imply that the re-invention is unnecessary. However, in the case of trauma, it may be necessary. It may also explain the ‘episodic amnesia’ that Herman refers to. Trauma is such a fundamental part of what it means to be human that it needs an equally powerful process to heal it. Creativity and hope are an antidote to trauma becoming traumatizing. Creativity requires a person to be fully present. The feelings involved in creativity are more powerful than learning about methods and facts. So, while we might learn from what has gone before we might also need to forget, so we can experience the kind of powerful creativity and hopefulness that is so important in the recovery from trauma. If we do remember what we have learnt, it is also important that we make something new from it. Creativity is a life force. Like play, creativity brings the authentic real self alive. Creativity is a playful state, in which people learn, experiment, and grow. Van der Kolk (2014, p.17) powerfully states the importance of creativity,

"Imagination is absolutely critical to the quality of our lives…. Imagination gives us the opportunity to envision new possibilities - it is an essential launchpad for making our hopes come true. It fires our creativity, relieves our boredom, alleviates our pain, enhances our pleasure, and enriches our most intimate relationships. When people are compulsively and constantly pulled back into the past, to the last time they felt intense involvement and deep emotions, they suffer from a failure of imagination, a loss of the mental flexibility. Without imagination there is no hope, no chance to envision a better future, no place to go, no goal to reach."

"Imagination is absolutely critical to the quality of our lives…. Imagination gives us the opportunity to envision new possibilities - it is an essential launchpad for making our hopes come true. It fires our creativity, relieves our boredom, alleviates our pain, enhances our pleasure, and enriches our most intimate relationships. When people are compulsively and constantly pulled back into the past, to the last time they felt intense involvement and deep emotions, they suffer from a failure of imagination, a loss of the mental flexibility. Without imagination there is no hope, no chance to envision a better future, no place to go, no goal to reach."

The human need to be imaginative, inventive, creative, and to discover is a vital energy in overcoming trauma. If we remember and know too much about what has gone before these qualities might not be so strong. Learning history does not have the same aliveness as living it. As Anne Alvarez said in the title of her paper on the recovery from child sexual abuse, there is ”The Need to Remember and the Need to Forget”.

Popularization of the word trauma

While the use of the word trauma has been used regularly throughout the last century its use has mushroomed in the last 20-30 years. The sociologist Frank Furedi (2004) researched the use of the word trauma in 300 British newspapers. He found that in 1994 the word trauma was used less than 500 times. In the year 2000, it was used over 5000 times. I expect that this trend has continued to multiply. Furedi and others (e.g., Hoff Summers and Satel, 2005) have highlighted how societies such as the UK and USA have shifted towards the image of a human, who is vulnerable rather than one who is resilient. Furedi argues that the exponential increase in attention to trauma also increases the risk of becoming traumatized by inviting people to see themselves as vulnerable, suffering, and ill. A key factor in whether someone becomes traumatized or not is the environmental context. This includes what we think and feel. Our perceptions of ourselves and each other are influential. Winnicott (1963, p.104) said,

The vast majority of people are not ill, though indeed they may show all manner of symptoms.

Seeing and thinking of a person as being ill compared with someone who has a symptom, which might have a purpose, is a subtle difference. And it is a difference that contributes to illness. We might argue that there are many more people diagnosed with ‘disorders’ today than there were 50 years ago or even 5 years ago. The first edition of the Diagnostic Statistics Manual, published in 1953, included 102 diagnostic categories. By the time of edition 5 in 2013, there were nearly 300 categories (Scot, 2022). The main change has been the inclusion of what Winnicott might have called a symptom to now being diagnosed as an illness. If there are 3 times the number of available diagnoses, we can expect a huge increase in the number of people now considered as having mental health illnesses or disorders. And in turn, people are further invited to think of themselves as being ill.

Beiner (2022) refers to the ‘mainstreaming of trauma’ and says,

We call this human experience ‘trauma’, and it’s absolutely everywhere in popular culture today. We talk of the ‘collective trauma’ of COVID. The ancestral trauma resulting from colonialism. Acute Trauma. Complex Trauma. Attachment Trauma. Trauma Bonding. Trigger warnings, safe spaces and trauma dumping. Trauma is historic. Personal. Universal. Above all, trauma is not what it appears to be.

Referring to Bonanno (2021) and others, Beiner (2022) argues that one of the problems of the focus on trauma is that it undermines the focus on resilience and other human strengths. There is much evidence of the continual underestimation by many psychologists of the human capacity for resilience and an exaggeration of vulnerability. One of the most obvious recent examples of this was following the 9/11 disaster in New York. Despite the warning of some psychologists to not overreact and allow the community to find its strength, thousands of psychologists and millions of dollars of counselling support were poured into New York. Most of it was never taken up by the citizens. The majority went through a normal healing process without a psychological intervention. Beiner states,

Hardly anyone sought out the (heavily advertised) free services, to such a degree that those running the campaign wondered whether it might be that people were avoiding therapy due to stigma. But even after physically sending people onto the streets to offer the therapy, the program had a very low uptake. Bonanno’s point is that the majority of us experience a traumatic event, go through a short period of symptoms as we process it, and then get on with our lives.

However, there is a significant difference between a big T trauma event and the little t traumas that are usually a part of complex trauma. Complex trauma may also have big T trauma events among the everyday little traumas. In a discussion with Beiner (2022) Bessel van der Kolk helpfully explains,

‘Little t’ trauma is a sloppy term and puts [those experiences] in a secondary role. In fact, what people call ‘little t trauma’, I think is really attachment trauma. It's about disrupted attachments. As long as you feel safe with the people around you, it's very unlikely you'll get PTSD…. we are collective creatures.

What people call ‘small t trauma’ is a very complex issue of people being ignored, people not being seen, kids not being responded to, kids getting slapped instead of being listened to. These are major issues that shape your personality and your identity…what people frivolously call ‘little t trauma’ are really the big issues of who we are as human beings and our obligations to take care of each other and to nurture each other in that regard.

The big trauma, horrendous things that leave you speechless? We are not bad at treating that. We spend a lot of time and effort into learning how to treat rape victims, how to treat torture victims. And we're moving in the right direction in that regard. But how to deal with having felt neglected, ignored and not seen as a child? We're not very good at prescribing what the best treatment for that is.

In the same way, too much attention to trauma can be unhelpful. It might increase anxiety and distract us from other important aspects of our lives and being. Winnicott pointed out that impingement during infancy can be traumatic and that this becomes compounded by further disruption when the mind becomes preoccupied with trauma. A child who is thinking about trauma cannot play. Though play may be a way of unconsciously working through or working out something. So, if we are excessively preoccupied with trauma, rather than facilitating what is healthy for development, such as play, we interrupt it.

Case example - Peter’s tic: Paying attention and not paying attention

Here is a brief and simple case example, about paying attention and not paying attention. Peter a 10-year-old boy has suffered several adverse childhood experiences, some of which were traumatic. He develops a pronounced nervous tic. This becomes a concern to various adults at family gatherings who remark upon it. They also suggest to Peter’s mum that she should refer him to a neurologist. The mum is anxious but does not react to the situation. Instead, she informally seeks some advice from a psychologist. The psychologist who is familiar with the family situation explains that this kind of thing is common, especially in boys and usually goes away on its own.

Peter tells his mum that he is worried about the tic. She listens to him and says no need to worry it is quite common for boys and it will most likely go away soon. Within a couple of weeks, the tics disappeared and never came back. During the same period, Peter told his mum that a counsellor had approached him at school and asked him if he would like to speak to a counsellor. She said this was because she knew about some of the family difficulties. Peter told his mum that this made him feel like he had something wrong with him. He said he didn’t want to talk to a counsellor. Peter did fine throughout the rest of his school and into early adulthood.

for boys and it will most likely go away soon. Within a couple of weeks, the tics disappeared and never came back. During the same period, Peter told his mum that a counsellor had approached him at school and asked him if he would like to speak to a counsellor. She said this was because she knew about some of the family difficulties. Peter told his mum that this made him feel like he had something wrong with him. He said he didn’t want to talk to a counsellor. Peter did fine throughout the rest of his school and into early adulthood.

This small example is a good illustration of what Furedi says about an excessive preoccupation inviting a person to perceive themselves as ill. Peter had this invitation coming from two directions, the family, and the school. Thankfully, his mum was able to resist the projected anxiety and not add to it. Sometimes, more and more attention as Furedi explains can have unwanted side effects. As the title of his book implies, Therapy Culture: Cultivating Vulnerability in an Uncertain Age.

This example reminds me of a point made by Perry and Szalavitz (2006, p.244),

Simply taking the time, before doing anything else, to pay attention and listen. Because of the mirroring neurobiology of our brains, one of the best ways to help someone else become calm and centred is to be calm and centred yourself – and then just pay attention. When you approach a child from this perspective, the response you get is far different from when you simply assume you know what is going on and how to fix it.

This is important advice. However, it is not always easy to pay attention. Dockar-Drysdale (1980s) sums up the difficulty and importance of listening,

"It is a sad fact that people do not listen sufficiently to children and what they say. They often say very important things in a very simple way and grown-ups are startled, frightened, or literally don’t hear what they have said, so remarks pass unnoticed. And often if these could be heard and understood it would make a tremendous difference to children. I often say to therapists here that listening is the most important thing they can do. We talk about therapeutic listening, which means listening to only what the child says and not to be thinking of anything else while the child is speaking."

important things in a very simple way and grown-ups are startled, frightened, or literally don’t hear what they have said, so remarks pass unnoticed. And often if these could be heard and understood it would make a tremendous difference to children. I often say to therapists here that listening is the most important thing they can do. We talk about therapeutic listening, which means listening to only what the child says and not to be thinking of anything else while the child is speaking."

Listening and paying attention is especially difficult when what we see and hear is distressing, painful, and disturbing. There is also the question of how we pay attention when there are many ways. Marion Milner who was a psychoanalyst and painter has written of ‘wide-angled attention’, which is receptive by not focusing. She says, “when I paint a tree in a field, I look at everything except the tree” (In, Phillips, 2019, p.14). Similarly, in therapeutic work, it is often helpful to look around the presenting symptoms and not just at them. With Peter, initially, too much attention was being paid to the symptom rather than looking around it. When less attention was paid, Peter’s tics went away. So, as well as paying attention being important, equally important is what we do after we have paid attention. For example, do we pay more attention or less? How do we respond to what we see, hear, and notice?

With all these issues and challenges, we have science and research to ground what we are doing, but the process of therapeutic work and ordinary human responsiveness often has more in common with art. This relationship between art and science is captured by one of the renowned neuropsychologists, Allan Schore, in the title of his classic book – The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy.

Too much protection Inevitably an excessive focus on trauma may increase our perception of vulnerability. For example, we might be more worried about the world being damaging and harmful. There is plenty of evidence that in some societies the anxious, over-protective, risk-averse ‘helicopter parent’ is now common. The problem with this is that it can hinder development, through a lack of challenge, and learning through experience. As we know, even an individual’s immune system is weakened by a lack of exposure to biological threats. Balance is needed. Lukianoff and Haidt (2018) summarize this need well with their book title, “The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting up a Generation for Failure.” Attention to trauma and the improvements made because of that are vast. However, we must not assume that being trauma-informed is like a never-ending upwards line, where it is always the more the better.

Research is beginning to emerge that highlights the risks involved in making that assumption. One example of the research has been on the use of ‘trigger warnings’. These are used to warn people of potentially anxiety-provoking images and words on a TV programme, advert, article, etc. A 2020 study (Jones, et al.) on trauma survivors suggests that they may increase anxiety. Beiner (2022) explains,

That study suggests that trigger warnings may be detrimental because they increase the narrative centrality of trauma among survivors. ‘Narrative centrality’ or ‘event centrality’ is very important concept: it means the degree to which someone identifies with their trauma, and to which it’s central in how they understand their own life. Decreasing narrative centrality, so that people see a life and identity beyond what happened to them, is largely seen to be therapeutically beneficial, according to multiple studies like this one. Increasing narrative centrality is then counter-therapeutic: it risks keeping people ‘stuck’ in their trauma.

This is the double-edged sword of increased cultural awareness of trauma. On one edge, it opens up more honest and vulnerable conversations about emotional suffering and mental health. On the other edge, it increases the narrative centrality of trauma throughout society. Considering we aren’t even clear what we mean when we use the word trauma, the result is a convoluted mess that presents potentially harmful views about mental health by overshadowing our innate resilience.

The concept of narrative centrality is interesting. Others, such as Van der Kolk (2014) have highlighted how a person’s perception of themselves, and an event (rather than the actual event) is a key factor in whether a person becomes traumatized or not. Van der Kolk has even shown that a person can become traumatized long after an event if the narrative around the event changes. Therefore, the more trauma becomes central to our individual and collective narrative there is a clear risk that this may contribute to increasing traumatization. This is exactly what Furedi (2004) has argued from a sociological perspective. The more we are invited to consider ourselves as traumatized, vulnerable, and ill the more likely it is that we will. Beiner (2022) argues,

What we believe ourselves to be is how we will experience ourselves. That is why we have to be so careful around how we conceive of ourselves, because we will make it true. If we see ourselves as resilient, flexible and robust beings, we stand a better chance of bringing that attitude into our lives than if we see ourselves as victims of giant, all encompassing force called trauma.

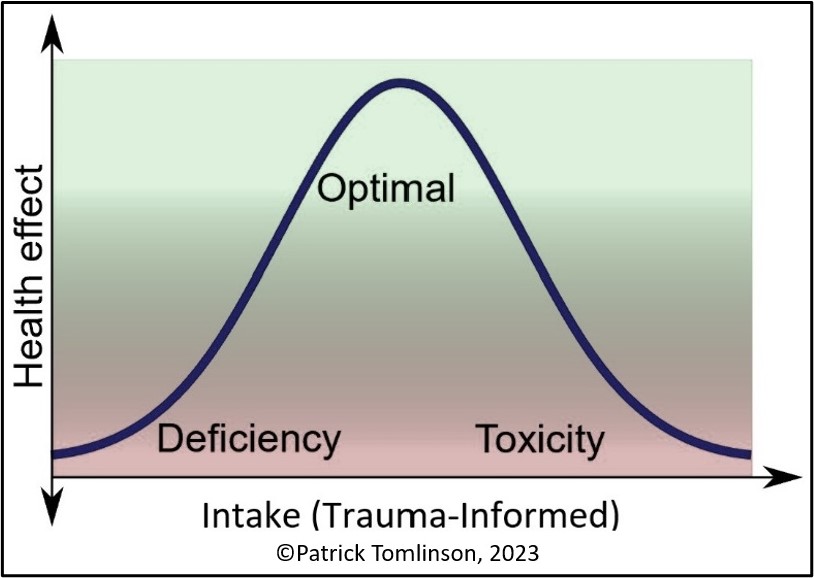

The balance of being trauma-informed and healthy would most probably look like a bell curve.

If we take the word ‘intake’ to mean how much information on trauma we ‘take in’ this analogy suggests that after a certain point, the effect becomes negative. As the over-emphasis on trauma and vulnerability can undermine health and resilience, at the far end of the spectrum trauma-informed can become misguided and toxic, like an unintended negative consequence. It may not be that the problem is with being informed but that the informed is not well balanced. There may be too much negative information and not enough positive. Such as the focus on Adverse Childhood Experiences ACEs) and the exclusion of Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs). Or the focus on damage rather than resilience. Or the harm of adversity rather than the transformational potential. The psychologist Stephen Joseph (2013) in his book, What Doesn’t Kill Us: The New Psychology of Posttraumatic Growth, argues that,

Posttraumatic reactions are not one-sided phenomena but multifaceted, encompassing both distress and growth.

Joseph argues that if we are to be appropriately trauma-informed we must include the concept of posttraumatic growth. Other influential psychologists such as the holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl (1959) in his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, have written powerfully about this. The worldwide transformational benefit of the work of Frankl and others has been huge and would not have happened without tragic circumstances. This does not undermine the real suffering and distress that is experienced in trauma, nor the need to ‘be with and in’ the feelings, and to make sense of and work through them. Resilience and the potential of transformation are not about denial but the maintenance of hope, learning, and growth. As with trauma, the meaning of words and concepts such as resilience and transformation can also be distorted unhelpfully. More recently neuroscientists such as Stephen Porges have also discussed and taught the concept of posttraumatic growth.

Joseph argues that if we are to be appropriately trauma-informed we must include the concept of posttraumatic growth. Other influential psychologists such as the holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl (1959) in his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, have written powerfully about this. The worldwide transformational benefit of the work of Frankl and others has been huge and would not have happened without tragic circumstances. This does not undermine the real suffering and distress that is experienced in trauma, nor the need to ‘be with and in’ the feelings, and to make sense of and work through them. Resilience and the potential of transformation are not about denial but the maintenance of hope, learning, and growth. As with trauma, the meaning of words and concepts such as resilience and transformation can also be distorted unhelpfully. More recently neuroscientists such as Stephen Porges have also discussed and taught the concept of posttraumatic growth.

Even if we are trauma-informed in a balanced way, a bell curve such as the above could be adapted for each person and each setting, such as an organization. A person’s and organization’s intake capacity are variable and changeable. Consideration of the situation and task is also necessary to determine the shape of the bell curve. For example, trauma-specific services, such as a counselling service, need more intake than a service where trauma is not directly relevant to the task, such as an ice cream shop. As trauma is part of human life, all organizations need some level of awareness, but the exact amount can only be evaluated according to circumstances. And it must also continue to be re-evaluated as human systems are always changing, whether they be families, organizations, or societies. It would be interesting to consider where you think you/and your organization are on a bell curve like this.

Adverse childhood experiences

Perhaps the best-known study on the long-term outcomes related to childhood trauma is the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Study (CDC, 2014, Felitti, 2002). The study was carried out in the USA and included over 17,000 people who were screened for ACEs. The ACEs included: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse: physical and emotional neglect; household dysfunction; mother treated violently; household substance abuse; household mental illness; parental separation or divorce; incarcerated household members. It was found that these ACEs tended to occur in clusters and the more ACEs the greater probability of poorer health and well-being, especially if a person had six or more.

The potential risks to well-being have been stated as serious health conditions, such as cancer and heart disease; behavioral health issues; psychiatric disorders; a shortened lifespan relative to the life expectancy of individuals without ACEs. While this research is thorough it may also be unintentionally misleading. Recent research (Baldwin, et al., 2021) has shown that while the ACEs study predicts group trends, there is not an accurate correlation between ACEs and outcomes for individuals. They state,

This study suggests that, although ACE scores can forecast mean group differences in health, they have poor accuracy in predicting an individual’s risk of later health problems. Therefore, targeting interventions based on ACE screening is likely to be ineffective in preventing poor health outcomes.

This is an important fact that can help prevent making negative assumptions about an individual who has suffered trauma and other adversities. The human brain is plastic. This means that what we experience can change the way we function. It means we have hope that recovery is possible. Many people have been relieved by the findings of this research. Most notably people who have suffered several ACEs and who felt the ACEs research implied future bad health if not a death sentence.

One of the obvious issues for individuals is that outcomes are equally affected by other factors and not just the number of ACEs. These other factors include the age of the individual when the ACEs occur, the number and quality of positive relationships, the unique constitution of the individual, and the precise nature of the ACEs (Hambrick, et al., 2018).

Positive childhood experiences

AAP (2014) explain the importance of considering adverse and positive factors together,

Adverse experiences and other trauma in childhood, however, do not dictate the future of the child. Children survive and even thrive despite the trauma in their lives. For these children, adverse experiences are counterbalanced with protective factors. Adverse events and protective factors experienced together have the potential to foster resilience.

Bethel et al. (2019) have researched how Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs) affect adult health. They argue that without this to go alongside ACEs we do not have a full and helpful picture. To gather information on PCEs they as respondents how often they,

1. Felt able to talk to their family about feelings

2. Felt their family stood by them during difficult times

3. Enjoyed participating in community traditions

4. Felt a sense of belonging in high school

5. Felt supported by friends

6. Had at least two non-parent adults who took a genuine interest in them

7. Felt safe and protected by an adult in their home

In summary, their research found that:

• Positive childhood experiences mitigate the effects of ACEs and buffer against toxic stress.

• Positive childhood experiences promote healing and recovery.

This perspective by AAP is a helpful reminder, as Beiner (2022) states,

We can forget that we are resilient creatures first and foremost.

Other confusions and difficulties

As well as the above confusions around ACEs there are other general confusions. What trauma and trauma-informed means have become confused. This is often the case when a word becomes so widely used in a short time. Perry and Ungar (2012, pp.6-7) stated the following,

Trauma is one of the most over-used, poorly defined concepts in neuropsychiatry. Popular use of the term "trauma" or "traumatic" has further confounded a physiologically meaningful or psychologically useful definition. People refer to an event as a trauma or as an event being "traumatic." Yet we know that there are multiple individually-specific outcomes from any group experiencing the same event. Indeed most events labeled "traumatic" ( e.g., school shooting, car accident, combat) don't appear to result in enduring negative mental health effects for the majority of individuals experiencing the "trauma."

Beiner (2022) argues how this over-simplification is linked to the popularization and mainstreaming of trauma,

Unfortunately, when something goes mainstream, curiosity and nuance often go out the window. The popularisation of trauma isn’t just a result of culture becoming more aware of mental health, it also serves political and cultural functions, and as such is prone to being twisted and manipulated.

Some would argue that the confusion has only grown further. The word trauma has become widely used for distress and upsetting events. Trauma is not the same as distress. Trauma is overwhelming, unthinkable, and associated with danger and helplessness. As well as a basic misuse of the word trauma, trauma is also often used interchangeably with traumatized. Trauma is common but becoming traumatized as a result is not inevitable. Trauma is part of ordinary life and development. Phillips (1995, p.49) goes as far as to say,

and upsetting events. Trauma is not the same as distress. Trauma is overwhelming, unthinkable, and associated with danger and helplessness. As well as a basic misuse of the word trauma, trauma is also often used interchangeably with traumatized. Trauma is common but becoming traumatized as a result is not inevitable. Trauma is part of ordinary life and development. Phillips (1995, p.49) goes as far as to say,

"Development is trauma, and trauma in its various forms is the subject-matter, the material of psychoanalysis."

Winnicott (1931, p.9) also emphasizes the ordinariness of trauma,

"Actual trauma, however, need have no ill-effect, as shown by the following case; what produces the ill-effect is the trauma that corresponds with a punishment already fantasized."

While trauma may “have no ill-effect”, traumatization, on the other hand, is the result of the trauma not being integrated as part of ongoing life. Traumatization may need a specialist intervention, or it may be healed through the experience of ordinary positive life experiences. Only when traumatization becomes stuck should it be considered a disorder. Even then we need to be careful that a diagnosis or label such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder does not pathologize someone as if they are ‘abnormal’.

As well as the word trauma being used widely to mean different things the same has occurred with the term trauma-informed. Some authors (Mieseler and Myers, 2013 cited in Wall, Higgins, and Hunter, 2016, Treisman, 2021) have attempted a helpful clarification by distinguishing a continuum of different levels – trauma-aware, trauma-sensitive, trauma-responsive, and trauma-informed. It can be argued that as trauma is common, all workforces should be trauma-aware. It is when we move closer towards workers being actively engaged with trauma, as in trauma-specific services, that we need to move along the spectrum towards a deeper level of being trauma-informed. And a trauma-specific service cannot work effectively unless the whole organizational setting is trauma-informed. Sandra Bloom creator of the Sanctuary Model goes as far as to say,

Trying to implement trauma-specific clinical practices without first implementing trauma-informed organizational culture change is like throwing seeds on dry land. (In, Menschner and Maul, 2016, p.3).

Needs-informed and healthy development

An excessive focus on trauma and trauma-informed may dominate in a way that undermines other important elements of healthy environments. For instance, it could be argued that other focuses are equally important such as understanding and responding to general human needs. One of my colleagues, Dr. John Gibson, has suggested a needs-informed rather than trauma-informed approach. This is potentially more inclusive, less stigmatizing, and less pathologizing. Everyone has needs. Other important human needs could be ignored if trauma is over-emphasized. We should attend appropriately to all needs, such as the need for healthy growth and development, as well as needs related to other difficulties that may be important but not traumatic. We should also ensure that we focus on supporting the development of people who do not appear to have difficulty. We need to avoid creating environments where the only way to get attention is by having a problem.

Often leaders and practitioners do very well by paying attention to others in a general way with inclusive practices, valuing and respecting others, listening, and caring, and creating safety. An over-emphasis on trauma can introduce unnecessary anxiety into systems that are working well. As if there is something we are not doing. The key question should be, are we achieving positive outcomes? Are people, whether our clients or colleagues getting better and developing? Being trauma-informed is important but is not more important than achieving positive outcomes. Therefore, in becoming trauma-informed we need to be careful to not lose focus on outcomes. Bollinger (2021) gives a good explanation of positive outcomes where practitioners are working in a trauma-informed without it always being explicit,

Therefore, while they did not use the language of trauma-informed care, they have naturally engaged in it. Furthermore, the young people interviewed also did not use the language of trauma-informed care, but also referenced the impact of what can be described as trauma-informed care. In essence, the staff participants noted that when trauma-informed practices are implemented, staff are better equipped to cope with the occurrences in the house and better maintain stability; the young people reported that they had enhanced outcomes from the staff being genuinely caring and involved with them.

Recovery and healing

As said, most experiences of trauma do not become traumatizing in the long term. The capacity of humans to recover and to help each other recover without specialist interventions is often underestimated. Sometimes this is referred to as spontaneous recovery. It is usually aided by a combination of a person’s internal and external resources. External resources are the people around the person, family, friends, colleagues, and community.

While we may talk of recovery it is important to acknowledge that the past trauma never disappears as if it never happened. A person works through the trauma and part of this means integrating traumatic experiences as part of one’s history and personality. So, we may consider recovery as getting back on track with the ordinary process of living and development. Kraybill (2015) prefers the term Trauma Integration,

I share the view of trauma scholar Robert Stolorow, that trauma recovery is an oxymoron. (Stolorow, 2011. p. 61). Things are never really the same after trauma. So, what then to name the place that can be achieved, where trauma is no longer the centre of experience and yet is acknowledged to be a part of ongoing reality? I call it Trauma Integration.

Winnicott (1963a, p.207) in his paper, Psychotherapy and Character Disorders argues,

"In the vast majority of cases the parents or the family or guardians of the child recognize the fact of the ‘let-down’ (so often unavoidable) and by a period of special management, spoiling, or what could be called mental nursing, they see the child through to a recovery from the trauma."

"In the vast majority of cases the parents or the family or guardians of the child recognize the fact of the ‘let-down’ (so often unavoidable) and by a period of special management, spoiling, or what could be called mental nursing, they see the child through to a recovery from the trauma."

Winnicott is highlighting how trauma is often integrated or recovered from as a part of ordinary experience. Possibly, the word recovery does not do full justice to the value of integrating the experience. Referring to more complex and challenging cases, Tomlinson (2020) states,

"Where trauma has been complex, from early childhood, it is not just one relationship or one incident that has been the problem for the child. It can be argued that the problem has been the whole of the child’s environmental context. In this sense, it may be that a service, which provides the whole context of a supportive network is most important for these children. Certainly, children who have experienced such environmental failure cannot be helped by individual therapy alone. They need to experience a primary home experience and everything that goes with it."

In these cases, a trauma-informed approach is needed. One that understands the nature of trauma, and how it can impact child development, a person’s functioning, and well-being. Most importantly, through a trauma-informed lens, it is understood what is needed for healing and recovery to take place. As Kezelman and Stavropoulos (2012, p.xxx) explain in their award-winning guidelines for the treatment of complex trauma,

Research now shows that resolution of trauma equates with neural integration. It also shows that longstanding trauma can be resolved, and its negative intergenerational effects intercepted. But for this to occur, mental health and human service delivery (i.e., as well as direct treatments) need to reflect the current research insights. Experience is now known to impact brain structure and functioning, and in the relational context of healing this includes experience of services.

Hambrick et al. (2018) recommend when treating complex childhood trauma,

Yet, even if a child’s early experiences are poor, improving future relational contexts may still help. To do so, however, we must think outside of traditional 50-minute therapy sessions toward ways to enrich a child’s entire relational world. Certainly, these findings highlight the complex ways developmental experience influences children’s functioning. We must never underestimate how experiences can both hurt and heal, and how positive experiences early in life can optimize development and be preventive. Continuing to explore associations between experiences and outcomes will allow us to construct and promote clinical work that is responsive to nuance, patient-centered and increasingly effective.

Key elements of a trauma-informed therapeutic approach

This subject is written about extensively (e.g., Treisman, 2021, Van der Kolk, 2014, SAMSHA, 2014a, 2014b, Barton, Gonzalez, and Tomlinson, 2012, Heller and LaPierre, 2012, among many others) so I will just outline some of the key elements involved. With all these issues, it is not just what we provide that is important – it is what the child makes from the environment and what might be on offer. We need to be careful to not believe that we can force-feed the child with our good intentions. We need to be available, to provide opportunities, but also to allow space for the child’s process, creativity, and potential for development. Referring to the work of Winnicott, Phillips (1988, p.74) reminds us of the importance of the child’s creative potential,

Winnicott is attentive to the kind of environment the child creates for himself, how he discovers and uses what he finds, as the essential indicator of emotional development.

The following are essential in facilitating trauma recovery, integration, and development, 1. Understanding the centrality of the child’s 24/7 lived experience in the recovery process. Working on establishing safety in all areas of the child’s life. 2. Being aware of the complex and often interwoven elements of the causes of trauma, such as abuse, neglect, violence, death of an important close person, serious accidents, injuries, illnesses, racism, disability, discrimination, etc.

3. Understanding the nature of complex childhood trauma. How it has impacted the child’s development. 4. What are the signs of trauma? And what kind of responses are most helpful?

5. Working on being attuned. Being aware of triggers and avoiding them where possible.

6. Strengthening any available family relationships.

7. Recognizing and enabling children to follow their interests and build on their strengths.

8. Enabling the conditions in which safe relationships can develop.

9. Understanding and using what we know about trauma from the long history in the field and the different perspectives. For example, attachment, psychotherapy, neuroscience, family systems, etc. Many helpful and practical, approaches can be used.

10. Supporting children to develop skills and self-mastery in different areas of functioning. For example, interests, self-regulation, education, and skills development.

11. Physical mastery and movement can be especially helpful to release emotion that has got stuck in the body and to help a child feel that their body is purposeful and useful.

12. Integrating into the local community and building life-affirming, supportive networks.

13. Providing consistent and healthy routines. A focus on healthy eating and drinking, good sleep patterns, and exercise.

14. Providing opportunities for positive new experiences. For example, nurture and enjoyable activities, especially with others.

15. Having clear boundaries and expectations, learning to take responsibility, and managing oneself with others.

16. Providing opportunities for communication and expression of feelings related to the past, present, and future. Integrating traumatic experiences through reflective processes.

17. Adults must endeavour to work in a consistent, joined-up, and congruent manner.

18. Providing all professionals involved with ample opportunity to process their experience and learn.

(Also, see Cook et al., 2005, Six Core Components of Complex Trauma Intervention, Treisman, 2021, NCTSN(a))

Achieving progress in these areas is challenging and complex work. It can be expected that as well as steps forwards there will also be many steps backwards along the way. This is because a person who has suffered complex trauma will not easily be able to make use of available opportunities. For example, they may need to test relationships and boundaries before they can feel safe enough to trust them. They will have major anxieties about change, suffer self-doubt, and sometimes lack hope, etc. Therefore, those attempting to provide support must be robust in their capacity to do this work and be part of a strong team approach.

Kezelman and Stavropoulos (2012, p.xxviii) state the hopefulness of such work,

"Research shows that the impacts of even severe early trauma can be resolved, and its negative intergenerational effects can be intercepted. People can and do recover and their children can do well. For this to occur, mental health and human service delivery need to reflect the current research insights."

A trauma-informed approach will understand these difficulties and others, as expressions of need. Behaviour has meaning and needs understanding. A trauma-informed approach, while needing clear boundaries and expectations, will not be judgmental, punitive, or reactive. People using a trauma-informed approach will have a good understanding of the research-informed theory. They will also understand the importance of other theories, such as attachment theory. The importance of relationships cannot be overestimated. Therefore, a trauma-informed approach is also a relational one. As Perry and Szalavitz (2006, p.230) state,

"Relationships are the agents of change and the most powerful therapy is human love."

Outcomes

Ultimately a trauma-informed approach must improve outcomes for service users. If it doesn’t it isn’t much use being ‘trauma-informed’, unless at least, further harm is prevented. As Stewart (1998, P.22) states,

Services are only of value if they are of value to those for whom they are provided.

This means we need to know what positive outcomes would look like. Some might be obvious, like a reduction in nightmares, panic attacks, and aggressive and self-harming behaviour. Others might be less dramatic but very important. Such as improvement in communicating feelings, better self-regulation, emotional development in general, improved enjoyment, better self-care, etc.

To know whether the therapeutic work, which means healing is working, the desired outcomes need to be clearly defined. The outcomes will vary according to the present situation of the service user, including their chronological as well as emotional age. The service user may also have specific outcomes that are important to them. What matters most to service users are outcomes that are going to help make their lives as fulfilling as possible. Continuing to explore associations between experiences and outcomes will allow us to construct and promote clinical work that is responsive to nuance, patient-centred, and increasingly effective.

As well as outcomes for service users we also need to consider outcomes for other stakeholders in a trauma service such as employees. We should pay attention to questions such as, are people developing well? Are there signs of vicarious trauma and burnout? Are sickness and absence high? What is the level of employee engagement? What is the level of staff retention?

In a healthy environment, trauma-informed or not, the most important outcome is people developing and flourishing.

References

AAP (2014) Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Lifelong Consequences of Trauma, American Academy of Pediatrics

Alvarez, A. (1992) Child Sexual Abuse: The Need to Remember and the Need to Forget, in, Live Company: Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy with Autistic, Borderline, Deprived and Abused Children, London and New York: Routledge

Baldwin, J.R., PhD, Caspi, A., PhD, Meehan, A.J., PhD, Ambler, A., MSc, Arseneault, L., PhD, Fisher, H.L., PhD, Harrington, H., BA, Matthews, T., PhD; Odgers, C.L., PhD, Poulton, R., PhD, Ramrakha, S., PhD, Moffitt, T.E., PhD, Danese, A., MD, PhD (2021) Population vs Individual Prediction of Poor Health from Results of Adverse Childhood Experiences Screening, in, JAMA Pediatrics, 2021;175(4):385-393, Published online January 25, 2021

Barton, S., Gonzalez, R. and Tomlinson, P. (2012) Therapeutic Residential Care for Children: An Attachment and Trauma-informed Model for Practice, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Beiner, A. (2022) The Truth About Trauma: Bessel van der Kolk, Rachel Yehuda and George Bonanno: How the Mainstreaming of Trauma is Changing Culture, The Bigger Picture

Bethell, C., Jones, J., Gombojav, N., Linkenbach, J. and Sege, R. (2019) Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels, in, JAMA Pediatr, 2019:e193007

Bloom, S.L. (1996) Every Time History Repeats Itself, The Price Goes Up: The Social Reenactment of Trauma, in, Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, Volume 3, Number 3, Brunner/Mazel, Inc.,

Bollinger, J. (2021) Placement Stability in Residential Out of Home Care: What is

Good Enough Stability? A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Social Work, Monash University, Australia

Bonanno, G.A. (2021) The End of Trauma: How the New Science of Resilience is Changing how we Think about PTSD, New York, Basic Books

Breuer, J. and Freud, S. (1893) On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena: Preliminary Communication (initially published in Neurol Zentralbl 1893; XII:4-10, 43-47); in, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Work of Sigmund Freud, London, Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1966, vol II, pp. 13-17

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2014) Prevalence of Individual Adverse Childhood Experiences

Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M. and Van der Kolk, B. (2005) Complex Trauma in Children and Adolescents, in, Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), p.390-398

Dockar-Drysdale, B. (1980s) An Interview with Barbara Dockar-Drysdale, John Whitwell: A Personal Site of Professional Interest

Dockar-Drysdale, B. (1990) The Provision of Primary Experience: Winnicottian Work with Children and Adolescents, London: Free Association Books

Farragher, B. and Yanosy, S. (2005) Creating a Trauma-Sensitive Culture in Residential Treatment, in, Therapeutic Communities, 26, 1, pp. 93–109

Felitti, V.J. (2002) The Relation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead, in, Permanente Journal, 6(1), 44

Frankl, V.E. (1959) Man’s Search for Meaning, London: Hodder & Stoughton, (Originally published, 1946)

Frankl, V. E. (1984) The Case for a Tragic Optimism (postscript to Man’s Search for Meaning), New York: Simon & Schuster, https://www.coursehero.com/file/91583972/Viktor-Frankl-The-Case-for-a-Tragic-Optimismpdf/

Freud, S. (1905) Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, in, Strachey, J. (ed.) (1978) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. VII, London: Hogarth Press

Freud, S. (1920) Beyond the Pleasure Principle, in, Strachey, J. (Ed. and Trans.) (1955) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 18, p.3-64, London: Hogarth Press (Original Work Published 1920)

Freud, S. (1926) Inhibitions Symptoms and Anxiety, in Strachey, J. (Ed. and Trans. 1959) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 20, p.75-175, London: Hogarth Press (Original Work Published 1926)

Furedi, F. (2004) Therapy Culture: Cultivating Vulnerability in an Uncertain Age, London and New York: Routledge

Hambrick, E.P., PhD, Brawner, T.W., PhD, Perry, B.D., PhD, MD, Brandt, K., NP, CNM, MSN, DNP, Hofmeisterb, C., Collins, J. (2018) Beyond the ACE Score: Examining Relationships Between Timing of Developmental Adversity, Relational Health and Developmental Outcomes in Children, in, Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, November 2018

Harvard Medical School (2005) Biology of Child Maltreatment, Harvard Mental Health Letter, in, ACE Reporter (2007) Adverse Childhood Experiences and Stress: Paying the Piper, Spring (2007), Vol. 1, 4

Heller, L. and Lapierre, A. (2012) Healing Developmental Trauma: How Early Trauma Affects Self-Regulation, Self-Image, and the Capacity for Relationship, Berkeley, North Carolina: North Atlantic Books

Herman, J.L. (1992) Trauma and Recovery, New York: Basic Books

Hoff Summers, C. and Satel, S. (2005) One Nation Under Therapy: How the Helping Culture is Eroding Self-Reliance, New York: St. Martin’s Press

James, B. (1994) Handbook for Treatment of Attachment-Trauma Problems in Children, New York: Maxwell Macmillan International

Jones, P.J., Bellet, B.W. and McNally, R.J. (2020) Helping or Harming? The Effect of Trigger Warnings on Individuals with Trauma Histories, in, Clinical Psychological Science, Vol. 8, No. 5, Sage Journals

Joseph, S. (2013) What Doesn’t Kill Us: The New Psychology of Posttraumatic Growth, New York: Basic Books

Kezelman, C. and Stavropoulos, P. (2012) The Last Frontier: Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Complex Trauma and Trauma Informed Care and Service Delivery, Australia: Adults Surviving Child Abuse (ASCA)

Kezelman, C. and Stavropoulos, P. (2018) Talking About Trauma: Guide to Conversations and Screening for Health and Other Service Providers, Blue Knot Foundation

Kraybill, O.G. (2015) Trauma Recovery is an Oxymoron

Levine, P.A. and Kline, M. (2006) Trauma through a Child's Eyes: Awakening the Ordinary Miracle of Healing, California: North Atlantic Books

Lukianoff, G. and Haidt, J. (2018) The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting up a Generation for Failure, New York: Penguin Press

Lyons-Ruth, K. (2003) The Two-Person Construction of Defenses: Disorganized Attachment Strategies, Unintegrated Mental States, and Hostile/Helpless Relational Processes, in, Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 2 (2003): p.105

Menschner, C. and Maul, A. (2016) Key Ingredients for Successful Trauma-Informed Care Implementation, Center for Health Care Strategies

Mieseler, V. and Myers, C. (2013) Practical Steps to get from Trauma Aware to Trauma Informed While Creating a Healthy, Safe, and Secure Environment for Children, Jefferson City: Missouri Coalition for Community Behavioral Healthcare

NCTSN (The National Child Traumatic Stress Network) Complex Trauma

NCTSN (a) (The National Child Traumatic Stress Network) What is a Trauma-Informed

Child and Family Service System?

Perry, B. D. (2003) Effects of Traumatic Stress on Children: An Introduction, The Child Trauma Academy

Perry, B.D. and Szalavitz, M. (2006) The Boy who was Raised as a Dog: And Other Stories from a Child Psychiatrist’s Notebook, New York: Basic Books

Phillips, A. (1988) Winnicott, London: Frontier Press

Phillips, A. (1995) Terrors and Experts, London and Boston: Faber and Faber

Phillips, A. (2002) Equals, London: Faber and Faber

Phillips, A. (2019) Attention Seeking!, Penguin Books: Random House, UK

Pynoos, R.S., Steinberg, A.M. and Goenjian, A. (2007) Traumatic Stress in Childhood and Adolescence; Recent Developments and Current Controversies, in, Van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A. C. and Weisaeth, L. (eds.) Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body and Society, New York: Guilford Press

Read, J., Fink, P.J., Rudegeair, T., Felitti, V., and Whitfield, C. (2008) Child Maltreatment and Psychosis: A Return to a Genuinely Integrated Bio-Psycho-Social Model, in, Clinical Schizophrenia and Related Psychoses, 2, 3

SAMSHA (2014a) A Treatment Improvement Protocol: Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services, TIP 57, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

SAMSHA (2014b) Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services Part 3: A Review of the Literature, TIP 57, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Santayana, G. (1905) The Life of Reason: Reason in Common Sense

Schore, A.N. (2011) The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy, New York and London, W.W. Norton & Company

Scot, T. et al., (2022) History of the Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Desert Hope Treatment Centre

Sinason, V. (2020) The Truth about Trauma and Dissociation: Everything you didn’t want to Know and were Afraid to Ask, Confer Books: London

Stewart J. (1998) Understanding the Management of Local Government, Longman

Stolorow, R. D. (2011) World, Affectivity, Trauma: Heidegger and Post-Cartesian Psychoanalysis, Routledge

Tomlinson, P. (2020) Mental Health Needs of Children in Care: Interview with Mr Patrick Tomlinson, by Leena Prasad, in, Institutionalised Children Explorations and Beyond, 7(2), pp.128-140, Udayan Care and Sage: India

Treisman, K. (2021) A Treasure Box for Creating Trauma-Informed Organizations: Volumes 1 & 2, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Ungar, M. and Perry, B. D. (2012) Violence, Trauma, and Resilience, in, Alaggia, R., Vine, C. and Waterloo, O.N. (Eds.), Cruel but not Unusual: Violence in Canadian Families (pp. 119–143), Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press

Van Der Kolk, B. A. (2005) Developmental Trauma Disorder: Toward a Rational Diagnosis for Children with Complex Trauma Histories, in, Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), p.401-408

Van der Kolk, B.A. and Newman, A.C. (2007) The Black Hole of Trauma, in, Van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A. C. and Weisaeth, L. (eds.) Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body and Society, New York: Guilford Press

Van der Kolk, B. (2014) The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma, New York: Viking

Van der Kolk, B. (2021) What is trauma? The author of “The Body Keeps the Score” Explains, Big Think, YouTube Video

Wall, L., Higgins, D. and Hunter, C. (2016) Trauma-Informed Care in Child/Family Welfare Services, Australian Institute of Family Studies

Winnicott, D.W. (1931) A Note on Normality and Anxiety, in, The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment, London and New York: Karnac Books (1990)

Winnicott, D.W. (1956) Primary maternal preoccupation, in, Collected Papers: Through Paediatrics to Psychoanalysis, London: Routledge (2001)

Winnicott, D.W. (1962) Ego integration in child development, in, The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment, London and New York: Karnac Books (1990)

Winnicott, D.W. (1963) Morals and Education, in, The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment, Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis: London (1972)

Winnicott, D.W. (1963a) Psychotherapy of Character Disorders, in, The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment, Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis: London (1972)

Files

- Download a Free PDF of this Article

- Download a PDF of Trauma-Informed Pratice Chapter

- Download a Free PDF of the Article and the Chapter

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting