ASSESSING THE NEEDS OF TRAUMATIZED CHILDREN TO IMPROVE OUTCOMES - PATRICK TOMLINSON (2008)

Date added: 29/12/20

This paper was originally published,

Tomlinson, P. (2008) Assessing the Needs of Traumatized Children to Improve Outcomes, in Journal of Social Work Practice, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 359–374

I joined SACCS in 2002 and became the Director of Practice Development. We created a unique integrated recovery programme for traumatized children and young people. It consisted of Life Story Work, Therapy and Therapeutic Parenting. The recovery programme had 24 clearly defined outcomes. Children's progress towards the outcomes was assessed as described here. The needs identified in the assessment then became part of the child's care plan. Sheree Kane (2007) in a national review of care planning, highlighted SACCS as one of two examples of best practice. It was a great example of what is now referred to as a therapeutic model. I would like to thank Mary Walsh, the inspirational founder of SACCS, for giving me the opportunity. We worked together, and with many others, to develop the foundations that had been laid into the SACCS Recovery Programme. As well as this article, five books were also published describing the SACCS Recovery Programme.

Reference

Kane, S. (2007) Care Planning for Children in Residential Care, National Children’s Bureau

ASSESSING THE NEEDS OF TRAUMATIZED CHILDREN TO IMPROVE OUTCOMES, PATRICK TOMLINSON (2008)

Abstract

This paper is about the development of an outcomes-based treatment approach in work with traumatized children and an assessment model to measure progress. It shows how a spider diagram is used to give a powerful, visual representation of a child’s progress. The work described has been carried out by SACCS – an independent UK organisation providing treatment based in residential and family settings for children who are severely traumatized by abuse and neglect. This trauma has had a massive impact on their development socially, physically, emotionally, academically and spiritually. The children have complex needs which are extremely difficult to work with. However, the potential for recovery from their injuries remains. I will use a single case study of a child to illustrate the process of assessment and measurement of recovery. The treatment approach used is broadly psychodynamic. The concept of an outcomes-based approach and the measurement tool described also has widespread relevance in Social Care.

(The paper draws upon a recently published book on assessment and planning – co-written by Tomlinson and Philpot 2007. I would like to thank Terry Philpot and Jessica Kingsley Publishers for their kind permission to use the material)

Keywords Trauma, Children, Assessment, Measurement – spider diagram, Recovery

Introduction

Children who are referred to SACCS* are between four and twelve years old on placement. Both boys and girls are placed in equal numbers and the average length of placement in a SACCS residential home is three and a half years. At the end of the placement, the child normally moves to a Local Authority or SACCS foster home. Children placed at SACCS are from a variety of ethnic backgrounds and are referred primarily by Local Authorities, occasionally in conjunction with Health and Education authorities. Referrals are from the UK (mainly England) rather than any specific area. SACCS has up to sixty children placed in its residential homes and twenty in foster placements. Due to the severity of abuse and neglect suffered by the children, there is generally limited ongoing contact with birth parents.

The children we care for have been denied their birthright of being protected and nurtured, and expert care is required if they are to fully recover from their trauma. Of course, we protect our children by ensuring they are no longer in danger, but just as importantly the work we do will also protect tomorrow’s children. It is widely understood that children who are severely traumatized by abuse and neglect may, without treatment, go on to abuse and harm others, becoming extremely inadequate parents and thus continuing the cycle of abuse and neglect. These children require an intervention that is focused on their needs, with an in-depth understanding of trauma and what is necessary to enable recovery.

Recently, Ward et al (2004) highlighted that there are a small number of ‘looked after’ children with a high level of support needs who are extremely costly to treat, often without positive outcomes. These children can experience frequent placement changes, have little contact with their families, and are often excluded from school. They are the young people whom society has most failed to protect, and the consequences for them as individuals, and for society, can be devastating. This is the very group of children SACCS works with.

Our first aim is to achieve placement stability and safety, and children who have had many previous placements (in many cases between ten and twenty) are normally held safely in placement with us for over three years. As Perry (2006, p.244) argues, work with children who have suffered early trauma,

... requires two things that are often in short supply in our modern world: time and patience.

He continues (p.245),

I also cannot emphasize enough how important routine and repetition are to recovery. The brain changes in response to patterned, repetitive experiences: the more you repeat something the more ingrained it becomes. This means that, because it takes time to accumulate repetitions, recovery takes time and patience is called for as these repetitions continue. The longer the period of trauma, or the more extreme the trauma, the greater the number of repetitions required to regain balance.

These are critically important points, supported by neurobiological research and are themes that underpin the SACCS approach.

Another of SACCS’ key objectives is to ensure that each child attends mainstream school so that achieving positive educational outcomes runs alongside social inclusion. Wherever possible we also pro-actively support contact with parents and family, enabling important therapeutic work to take place through the maintenance of significant natural bonds. Most importantly, the central thrust of our treatment model is a therapeutic, integrated programme of therapy, life story work and therapeutic parenting. Therapeutic parenting provides a structured means for a severely traumatized child to move from insecure to secure attachment, to fill gaps in their formative experiences and to work through feelings associated with their trauma.

SACCS have put an outcomes approach based on the child’s recovery at the centre of their work. I aim to show some of the benefits of this. First of all, I will introduce you to Jack who is typical of the children placed at SACCS and who was seven years old when he was referred by his Local Authority. Early in his life, social services were alerted to his case, due to several admissions to hospital for treatment of injuries, such as a fractured arm and as a result of domestic violence between his parents. When Jack was three, following the separation of his parents, his mother alleged that he had been sexually abused by his father. During the next year, Jack’s mother was unable to look after him and his siblings and due to the levels of neglect, the children were taken into care. The following comments were recorded by practitioners during his first few weeks at SACCS.

Jack

He cannot accept being found responsible for his actions - he becomes sulky and withdrawn showing little remorse – it is always ‘everybody else’s fault’. He has completely distorted thinking and escapes into fantasy – he feels indestructible in this way.

He is always asking ‘why?’ even when something has been explained to him. His learning is delayed by approximately three years. He continually says, ‘I’m bored’ and is unable to concentrate. His levels of regression have grown, and teachers are concerned about this.

The intensity of his emotions is overwhelming for him and often for those with him. Some adults are uncomfortable with hugs from him as they feel sexualised and overbearing. He cannot express his feelings appropriately – when he is not being aggressive, he always says what he thinks adults want to hear.

The only feeling he can recognise in others is anger. He is controlling, dominating and aggressive with children at school but complains of being bullied.

He often shows extreme emotional distress which is discharged very physically and violently. He bites his arm and scratches himself to gain attention. He will throw himself around when very distressed and hits himself on the head with objects.

He is drawn towards females but also physically attacks them and will treat them as inferior. He is fearful of men and particularly at bedtime. He avoids any sense of closeness or affection with adults.

He becomes excited by delinquent behaviour and this often feels sexualised. When he becomes sexualised, he will hit himself on his head and pulls his ears.

As can be imagined from these comments Jack’s early life was one of huge deprivation and abuse, and unfortunately many breakdowns in foster placement following that.

SACCS Integrated Treatment Model

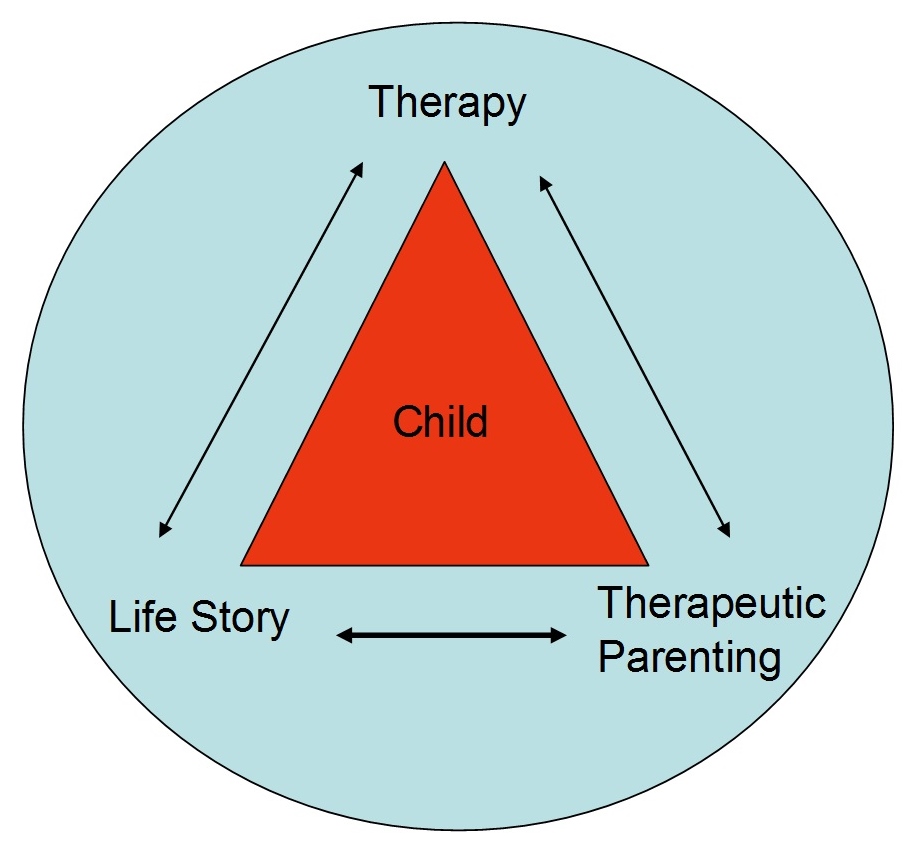

SACCS works with children like Jack by providing an integrated model of therapeutic parenting in the residential home, as well as individual therapy and life story work outside of the home setting. Briefly, therapeutic parenting primarily holds and works with the child’s present and future; therapy the child’s relationship between his external and internal world; and life story the child’s past and works on the present understanding. These three strands of therapeutic work are strongly connected, so that everyone involved, works together as a team in supporting the child’s recovery. Issues such as confidentiality are held by the whole team rather than ‘split off’ into professional factions. Together, the child’s therapeutic parenting team, therapist, and life story worker are called the recovery team.

Integrated Approach to Recovery

Containment of the child in the SACCS programme allows children to test out their understanding of previous life experiences, enabling them to reframe these as well as their behaviours. As they test out new behaviours and understanding they have the opportunity to reflect and positively alter their external and internal processing. Safety through the process enables children to consider their behaviour and reflect with caring adults on the causes and effects as well as their own actions and reactions. The children and young people placed at SACCS require the consistency and connectedness provided by the integrated process and this means that there is a high level of interdependency between the three different services.

Defining the SACCS Outcomes

In recent years and with the advent of ‘Every Child Matters (DfES, 2004)’ we have seen a shift in service provision focus from process to outcomes. For our purposes, the Oxford Dictionary (1992) definition of an outcome, as a result, the consequence or end product, is too broad and only helpful in the sense that it orientates us onto the results of our actions rather than the action itself. To use the notion of outcomes more positively and usefully, we need to make two further distinctions. Firstly, we should narrow our focus to achieving positive outcomes and secondly, the outcome needs to be identified by the recipient as positive. Willis (2001, p.139) reminds us of the statement, which the Department of Health initiatives of the 1990s were founded upon,

Social care services are likely to be most effective when they are orientated towards outcomes: concerned with, designed, provided and evaluated in terms of the results experienced by the people for whom they are intended.

We must always keep in mind that all our work, such as training, supervision, assessment and consultancy is only of any use if it contributes to the delivery of the desired outcomes for children. It is often easier to measure inputs, processes and outputs than outcomes. In a recent study on Routine Outcome Measurement (ROM) in UK Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, Johnston and Gowers (2005), found that less than thirty per cent of services carry out ROM and cite resource issues as the main obstacle.

Involving the Service User

In the case of children, it is not always straightforward to determine who the user is for whom the outcomes are intended, as there can be many stakeholders involved. For example, the Local Authority, family members and individual children. While we might expect an adult to define the service they would like and what they expect from it, this can be at odds with the normal process of child development. Parents might listen to their children, but they would normally assume responsibility for decisions about the child’s best interest. The exact nature of this varies in practice and law according to the child’s age and understanding. I would suggest that the model should be one of including children as much as possible, in stating their concerns, wishes, likes and dislikes but the responsibility for defining the outcomes of the service lies with the parents and/or local authority. They should hold the service provider to account in delivering the agreed outcomes. The following point made by Willis (2001, p.143), can be seen as particularly relevant to children,

Users may feel dissatisfied because the service was imposed on them, even though it might have a beneficial outcome.

However, the focus on issues of choice for the user, or being involved, should not detract from determining whether the user has benefited from the service. When measuring outcomes, it is also important that we measure equality outcomes. In other words, whether the outcomes are achieved equally by different groups receiving the same service, e.g. different gender and ethnic groups.

In 2002 SACCS began to define outcomes in work with traumatized children. We began by asking, how would we know if a child’s treatment had been successful, what would a ‘recovered Jack look like’?

Recovery for the children at SACCS is summarised by the child having internalised their attachments and consolidated their emotional development to a point where these can be successfully transferred to other environments and relationships and that they have the potential to achieve to full ability in all aspects of their life (Pughe and Philpot, 2006, p.112).

The focus of work is on enabling children to achieve positive outcomes.

We arrived at 24 Outcomes for Recovery, for example,

When the child;

- has a sense of self – who they are and where they have been.

- understands their history and experiences.

- can show appropriate reactions.

- has developed internal controls.

- can make use of opportunities.

- can make appropriate choices.

- can make appropriate adult and peer relationships.

- can make academic progress.

- can take responsibility.

- has developed conscience.

- is no longer hurting themselves or others.

- is developing insights.

- has completed important developmental tasks.

- has developed cause and effect thinking.

- understands sequences.

- has developed motor skills.

- has developed abstract thinking.

- has improved physical health.

- has normal sleeping habits.

- has normal personal hygiene.

- has normal eating behaviours.

- has normal body language.

- has normal self-image.

- can make positive contributions.

We have defined the meaning of each outcome (Walsh and Tomlinson, 2006), for example:

When the child has a sense of self - who they are and where they have been - This means that the child has a sense of their own identity, and culture regardless of creed, race, nationality, or religion, especially if there are also issues of disability and/or gender. They understand about their family of origin, have worked through what they love, hate, are angry about, are frightened of, and are not in denial. They know who they are in relationship to important people in their past and significant people in their present. They have integrated their past experiences into their present reality. Their personality is clear and intact. The child is living mostly in the present. Their past is no longer controlling their lives.

When the child can make positive contributions - This means that the child can respect themselves and their opinions as a creative force. They can ask for what they want and intervene appropriately in a positive way in other interactions. They can view the world as a healthy, safe and exciting place that they have a part in creating and influencing.

The 24 Outcomes are relevant and beneficial to children. They are also so intricately connected to the fundamental human needs of safety, happiness and development that there can be little doubt as to whether the outcomes matter. We know that achievement of these outcomes should bode well for the child’s future, though, the child may neither fully understand their significance, nor be willing to acknowledge whether an outcome matters to them. Having defined the outcomes, SACCS identified the necessary tasks to be completed to achieve each outcome and then wrote guidance on ‘how to’ support and enable the child in this process. This is all incorporated into the SACCS Recovery Programme. Therefore, for each outcome, there is a series of tasks and for each task a series of ‘how to’s’. therapeutic parenting, therapy and life Story all work towards the same outcomes but achieve this through their specific tasks and ‘how to’s’. For example, under the outcome of Improved Physical Health, two of eight tasks in therapeutic parenting are,

- Ensuring personal hygiene needs are met in a caring and loving way so that the child learns that caring for their bodies is part of loving themselves.

- The house will be run on healthy routines so that the children will be able to relax into the boundaries and predictable timetable of the house. For chaotic children, this is especially important as it provides a sense of security and being anchored. Building in anchor points, routines and limits are necessary for each house to hold children emotionally, contain their anxiety and give appropriate space for individual choice and autonomy.

The following ‘how to’s’ are listed under the first of these tasks,

- Understanding the child's history, and in particular formative experiences concerning personal hygiene.

- Using the recovery assessment to understand the child's stage of development, and how experiences of trauma have impacted on this and their physical wellbeing.

- As part of the therapeutic parenting team, formulating a plan to meet the child's personal hygiene needs in a loving and caring way, while taking account of the difficulties that might be involved. For example, being sensitive to the child's feelings of shame around intimate care.

- Ensuring that all daily routines around the child's personal care, such as washing, bathing, teeth cleaning, hair combing, nail cutting, are done reliably and consistently.

- Using every opportunity in daily living to show children that their health is valued, and their bodies deserve to be cared for.

- Reflecting the importance of personal care in the home by making sure that there is an emphasis on enjoyment in a child-centred way, for example by providing bath toys and bubble bath.

- Working closely with the recovery team so that everyone is aware of what is happening for the child.

The SACCS Recovery Programme provides an extensive resource to help practitioners think around their work with children and to provide helpful possibilities. However, it is not intended to pre-determine what the specific approach towards an individual child should be. We must never lose sight of the uniqueness of each child by looking for overly prescriptive solutions to complex matters. As Thompson (2000, p.80) argues,

If we expect theory to provide ready-made answers to the questions practice poses, we are misunderstanding not only the nature of theory but also of practice. Theory cannot provide simple answers which tell us ‘how to do’ practice. Theory can only guide and inform. Theory, practice and the relationship between them are all far too complex for there to be a clear, simple and unambiguous path for practitioners to follow. Theory provides us with the cloth from which to tailor our garment, it does not provide ‘off-the-peg’ solutions to practice problems.

Assessment

Once outcomes have been identified there needs to be a reliable way of measuring or assessing progress towards those outcomes. Glaser and Pryor (p.88) have used the concept of clinical usefulness in relation to assessment processes,

This is a summary of how useful the assessment might be in a clinical setting, based on what has been said about its established reliability and validity, and an assessment of the ease with which it can be administered. This assessment of usefulness considers the time and resources needed to train and administer the assessment and the result it yields. If the results are not easily interpretable, or the test is very difficult or costly to administer and score, an assessment is not deemed to be clinically useful.

Given the amount of resource that can be required by an assessment process, it is important to have a clear sense at the beginning of what is hoped to be achieved. An important starting point is to be clear how a specialised assessment fits within the wider context. In the case of children’s services, it is important to work within the parameters of the ‘Every Child Matters’ outcomes and the Common Assessment Framework. The SACCS assessment process aims to: identify where children are in their development; measure and evidence progress; enable plans to be worked out within the context of achieving outcomes and to provide a clear format for communication about outcomes.

Using the assessment process to think about the child together is also especially important for these children who have had lives where the adults caring for them have not been able to think about them and their needs. In many cases, the child’s primary carers have only been about to think about the child in terms of meeting their own needs. So, we are providing the child with the experience of being thought about in a positive and caring way. Through assessment, we have a better understanding of the child, which enables us to respond more effectively to him. For the child, the experience of being understood may also be new and is vitally important to their recovery.

The process of using a shared assessment format can help those involved to develop a shared language and approach, which is very valuable when working in multi-disciplinary teams. At SACCS it has helped to integrate the work of therapeutic parenting, therapy, life story so that everyone is working together, consistently and in a focused way to achieve the same aim. Models like this have been referred to elsewhere by Diana Cant (2002) as ‘Joined up Psychotherapy’ or by John Woods (2003) as ‘Multi-Systemic Therapy’. It is not a question of which therapeutic approach is the best, but of how the different approaches can combine to achieve the most positive outcomes for the child. A good assessment should lead to clarity about what we need to put in place to achieve positive outcomes and provides a way of evaluating our approaches - what works and what does not. To summarize, as Adrian Ward (2004) has said, ‘You can have assessment without treatment but you certainly can’t have treatment without assessment.’

SACCS Assessment Format

At SACCS an assessment form is used, looking at the child under six broad developmental areas, based on the 24 outcomes. These are Learning; Physical Development; Emotional Development; Attachment; Identity and Social & Communicative Development. There are a series of questions under each area. For example, under the section on learning there are questions based on the outcomes related to making use of opportunities; making academic progress; taking responsibility and cause and effect thinking. An example of an assessment question is - Understanding of Cause and Effect [e.g. Does he understand how one thing leads to another? Does he understand how different actions and behaviours have different effects?]

The child’s therapeutic parenting team, therapist, and life story worker, each carry out their assessment, scoring the child against the questions and providing anecdotal evidence to support their score. Therefore, the assessment is both quantitative and qualitative. This ‘evidence’ is a very useful record – helping to build our understanding of where the child is now and how they are developing over time. To assess a child and score her progress it is necessary to think about the developmental norms for children of similar ages. A score of,

1 = Severe Concerns; poor functioning in this area

2 = Substantial concerns; some signs of progress but a range of aspects to address

3 = Moderate concerns; one or two aspects to address

4 = Positive functioning in this area, with possibly minor concerns

To ensure consistency in our assessments of children we must maintain a balanced view of the child, keeping specific incidents or aspects of behaviour in perspective alongside the child’s overall behaviour. We reflect on the description of a child’s behaviour and then focus our thoughts on what we understand this to mean. All behaviour has meaning, for example, ‘attention-seeking’ behaviour may be ‘attachment-needing’ behaviour. The aim is to clarify the areas where a child needs more help and support to progress their recovery. When considering a child’s progress, we recognise that growth is not always linear. A traumatized child finding containment, warmth, safety and positive caring may need to regress to progress. Similarly, a child may ‘take two steps forward and one back’. To support consistency in assessment, scoring guidelines are provided. Under each of the assessment questions, there are four sets of scoring indicators, one for each of the assessment scores. The child is scored against the indicator set that most closely matches the child. This does not mean that the child’s behaviour and development will exactly match with the indicator, but the one chosen is closest to how the child generally is. For instance, the indicator sets under the Cause and Effect question are,

- Has no concept of cause and consequence. His actions are for immediate gratification, which overrides any concern about the effects of his behaviour. Has no awareness of how other people feel.

- Has some understanding of the effects of his behaviour but this is not reflected appropriately in his actions. Needs constant support, reminders and explanations.

- Can be aware of the effects of his behaviour. Has begun to develop an understanding of cause and effect. Needs support in making such decisions but can reflect on the causes of his actions.

- Is aware of how one action can lead to another and can change his behaviour to accommodate this. Understands how his behaviour can affect others and mostly uses this positively.

These indicators provide a sequence of progress towards a child’s achievement of the outcome ‘has developed cause and effect thinking’. There are four stages of progress identified and moving between them takes considerable time. If it is felt that a child is between two of the scores, half points can be used. As Alvarez (1992, p.151) has reminded us,

... recovery can be a long, slow process, particularly for the children who have been abused chronically at a young age.

We also evaluate the child’s ‘Internal Working Model’, using Bowlby’s definition. For example, does the child believe he is good or bad, lovable or unlovable, competent or helpless? Are his caregivers responsive or unresponsive, trustworthy or untrustworthy, caring or hurtful? Is the world around him safe or unsafe; and is life worth living or not worth living? To support our understanding of the child, the life story worker provides a thorough synopsis of the child’s life history, including important information on different family members.

The assessment forms are completed every six months and a Recovery Assessment Meeting is held, involving the whole of the recovery team to consider their assessment and from that, develop a recovery plan with the child to address his needs. The first hour of the meeting is focused on understanding the child, her development, achievements and difficulties. The last half hour of the meeting is concerned with developing a recovery plan for the next six months work. The assessment meeting is an excellent opportunity to think together about the child. As Ward (2004, p.9) has argued,

What matters most is that the whole team is engaged both in the process of assessment and in the process of treatment.

At the beginning of the meeting, a picture of the child is displayed by a projector. The picture is specially chosen by the child and is a powerful way of enabling everyone to literally ‘hold the child in mind’. It is often illuminating to see how the child sees themselves or wants to be seen, and how this changes over time. Each part of the recovery team, compare their assessments, considering specific issues about the child’s development and progress being made, and agree upon how they will address key matters during the next 6-month plan. This can then be worked on in detail in following team meetings and with the child.

The meeting is chaired by a senior practitioner who is not part of the child’s recovery team. This provides an external perspective, helping to clarify different points of view, establishing a consistent approach to the assessment and following plan. An important task for the chair is to check that the assessments are reasonably objective and that the scores are a fair reflection of the child. Due to the difficulties involved in the work, the feelings of those involved can become highly subjective. The scoring guidelines and role of the chair both help to contain this tendency within acceptable limits. Alongside this, the significant amount of data that is recorded about each child, daily, also helps to balance subjective feelings with tangible realities, such as school attendance, physical health, number of difficult incidents and positive achievements. The chair is also able to focus on the dynamics of the meeting itself, for example, the feelings and interactions between the practitioners and use this to further understanding of the child. On occasions, an observer is used in the meeting to specifically pay attention to the process of the meeting. The person in this role makes no direct contribution to the meeting but has an opportunity when the meeting breaks after an hour to give feedback to the chair. It seems that this role adds to the emotional containment of the meeting, and insights which may have been missed are often contributed during the interval.

One of the key aims of the assessment process is to agree on a plan for work with the child over the next six months. For example, if the child is finding it extremely difficult to put feelings into words, enabling the child to communicate may be an important aspect of the work in therapeutic parenting, therapy and life story work. Once the practitioners feel clear what the child needs to progress, they will discuss this with the child, enabling her to identify her outcomes in the process. For example, a child might say who they would like to talk to, how and when by. In this way, ‘big’ outcomes can be broken down into ‘smaller’ achievable outcomes.

The plan identifies key aspects of a child’s daily living, relationships and engagement in therapy and life story work that warrant individual and more intensive focus and intervention. The assessment thus informs and is realised in the treatment plan (Pughe and Philpot, p.120).

Spider Diagram

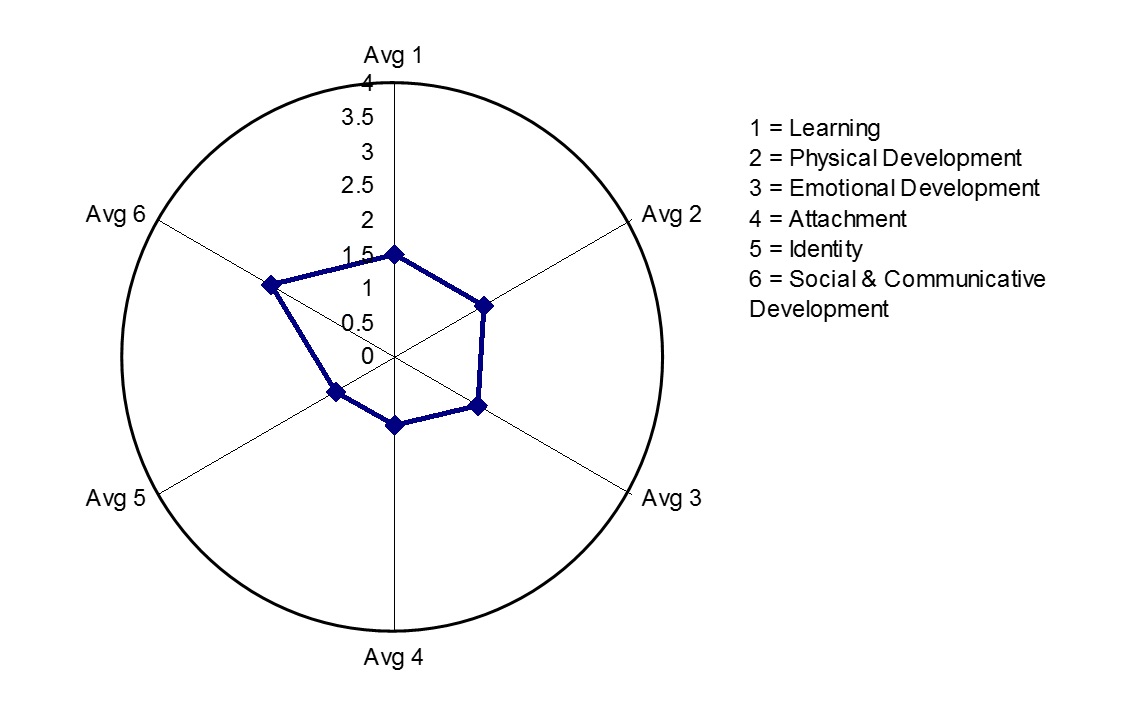

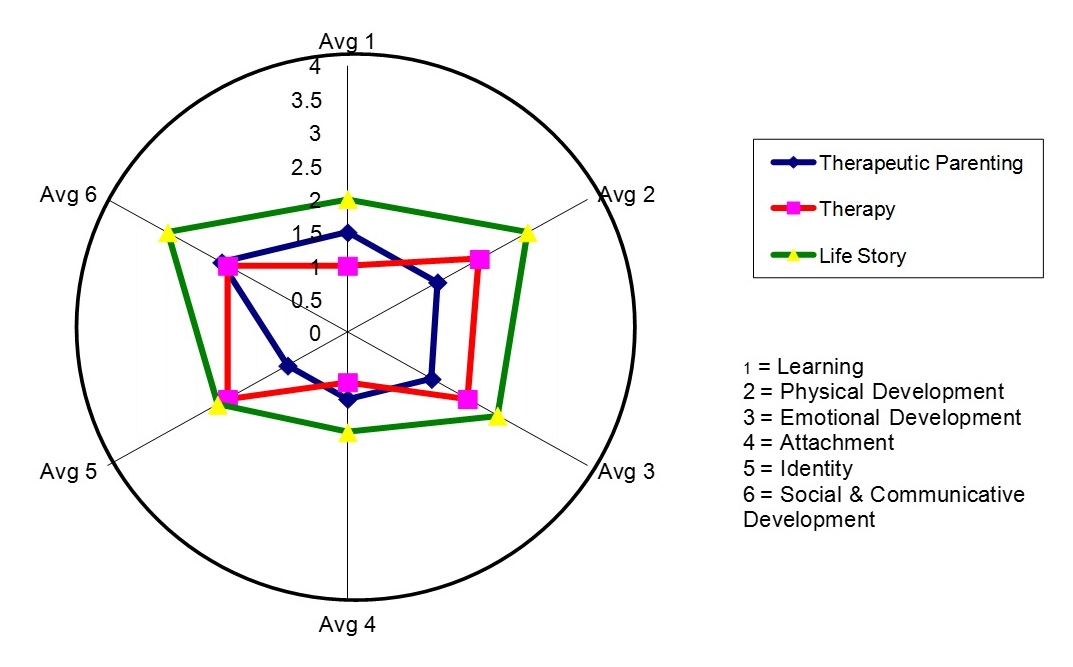

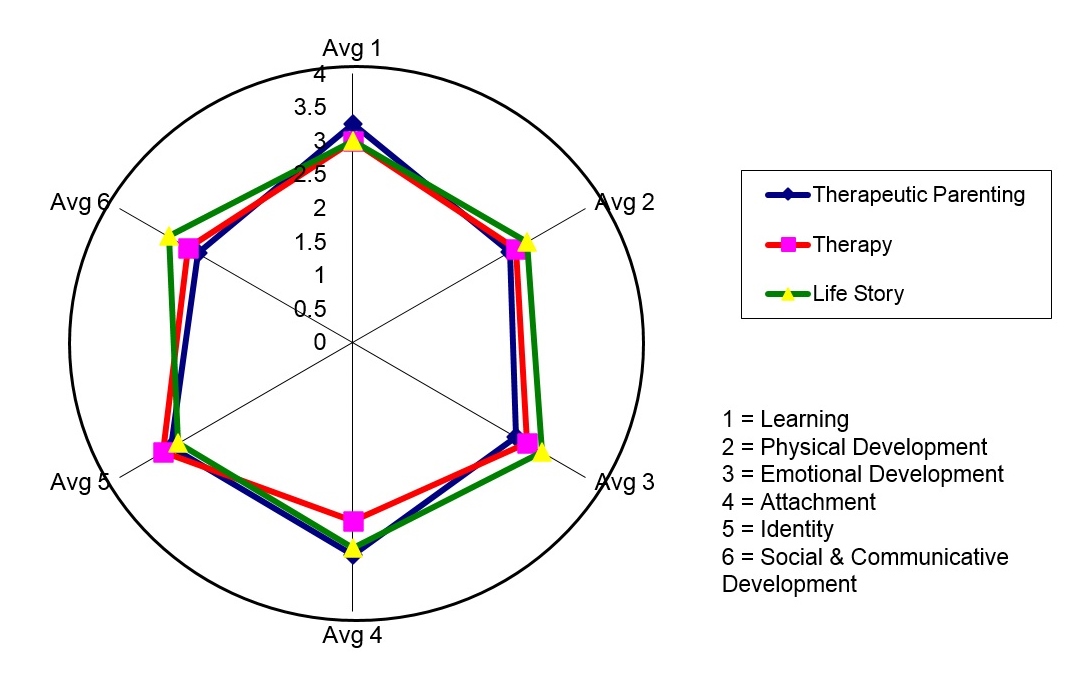

To help get a picture snapshot of the child and her development we use a spider diagram, sometimes also called a radar diagram.

The six developmental outcome areas are represented by the six axes. The child’s score is plotted along each axis and the points are joined together to create a shape within the circle. This is done by taking the average score (between one and four), from the series of questions under each area. For example, the average score of the four questions under learning might be 1.5 and this will be plotted on axis one. The points on the six axes are joined together creating a shape representing the child’s current stage of development. When we were developing our model and looked at different ways of visually representing the child’s progress, the spider diagram was by far the most popular. I think this is partly because it symbolically captures the sense of the healthy child and the small or damaged child within. This could be seen as the small ‘ego core’ of the child as it grows over time, towards a ‘well-rounded child’. The outer circumference represents where a child with ‘normal’ or healthy development could be and the shape of the assessed child shows where the gaps are and how far there is to go. The greater the gap between the circumference and the inner shape the greater the therapeutic support the child will need. This gap is similar to Vygotsky’s (1978) concept of the ‘Zone of Proximal Development’, or, how the child can function on her own compared to how she could function with the input of others (Mooney, 2000). The support necessary to enable the child to move from where she is now to where she could be, Vygotsky termed ‘scaffolding’. In our context, this is where the therapeutic work takes place. The time we need to help a child reach her potential with us is normally three and a half years or more. The scores from the three parts of the recovery team are plotted on the same diagram and this creates an instant and striking view of how the child is perceived and functions in the three different areas.

This is the spider diagram of Jack’s first assessment

As we can see, everyone sees a child who is extremely damaged in his development and who has huge needs. However, there are differences in the 3 pictures. We often see this with a child like Jack – a child that Winnicott (1962) may have called ‘Unintegrated’, or Solomon and George (1999), a child with ‘Disorganised Attachment’. He will be different things to different people at different times, compliant one minute and chaotic the next. As a reaction to his traumatic experiences, Jack had developed a protective shell which he presented with a degree of success to the life story worker. Aspects of this were maintained in the relationship with his therapist, though the therapist also saw serious damage to his development. The therapeutic parenting team who the child lived with were exposed to the small and extremely traumatized child inside the protective shell. Through the integrated work of the recovery team, these fragmented aspects of Jack’s fragile personality are held together and reflected back to him in a consistent way. This enables the child to gradually internalise a more balanced and connected, rather than a fragmented or split sense of self.

Let us now look at how Jack is – three years on. These are comments recorded by those working with him recently,

There are hints that he can feel empathy - sometimes he shows concern for others, he often makes sorry cards. When he has had time to think about his actions, he can feel appropriate guilt, which can lead to reparation.

He is more secure in his attachment with Julie and allows her to provide him with nurturing experiences. He is less anxious around men and has begun to identify positively with Mark.

He now settles well at bedtime. He sleeps deeply and gets lost in his dreams. He likes a variety of food and takes opportunities to try new things. He has good manners and is sociable at the table. He is not so anxious at getting his share. He has good health and does not worry as much as he used to. However, he does have an issue with feeling fat and he does not want to grow - maybe a fear of growing up? Or anxiety that he will be like his dad?

He can communicate quite well with adults and is beginning to talk about important things. He will sometimes chatter to take up ‘thinking space’. He has good use of language, at times trying to be an ‘adult’. He has come on greatly in his interactions with others, though he still finds it difficult to compromise. He is sexually aware and no longer shows inappropriate behaviour.

He normally takes a pride in his appearance and likes to look smart. He will sometimes damage his possessions when angry. His self-esteem is growing, and he takes a pride in his schoolwork. He is more confident when faced with new challenges.

He can play with others – creatively, imaginatively and competitively.

He remembers lots about his history and is coming to terms about his role in this. He identifies with being a boy and enjoys male sporting activities such as football. He is physically well co-ordinated and enjoys playing ball games. He is proud of his Welsh nationality.

Jack’s sixth assessment after two and a half years

This data suggests that Jack is on the journey to recovery. The zone of proximal development is smaller; he needs less input to function to his true potential. There are still areas of difficulty and underlying fragility. We also see that Jack’s behaviour is more consistent, at different times, with different people in different situations. He is becoming integrated and his attachments are more secure. However, recovery is not a cure but a lifelong journey. As Dockar-Drysdale (1993, p.50) has said,

I really want to jettison the concept of ‘cure’ at once, and replace this by ‘evolvement’.

To consolidate Jack’s growth, he will need a carefully planned transition into a family placement, providing continuity in his care and an understanding of his needs. The transition should happen at the child’s pace, involving close work between the present and new carers.

Conclusion and Further Development

The SACCS assessment process has now been running for over four years and has proved to be a useful treatment tool. In a recent survey involving fifty practitioners, ninety per cent agreed that ‘the assessment and plan process helps children to achieve positive outcomes’ and ninety-eight per cent agreed that ‘the assessment and plan process has enabled therapeutic parenting, life story, and therapy practitioners to work more effectively together as a recovery team’. However, only fifty per cent agreed that ‘the assessment and plan process has enabled children to be more effectively involved in their recovery’ and twenty per cent disagreed. This is an area that needs to be developed. SACCS is presently working on a format for children to evaluate their progress; more clearly define their outcomes and give feedback on the service provided. Potentially this could lead to the child’s picture of their progress being plotted on the spider diagram. This would provide another illuminating piece of information. For example, how would we consider a child whom practitioners considered to be well developed but the child’s perception was much less positive? Consistency between the recovery team’s view of the child and the child’s view could be an important factor in evaluating recovery. As well as adding the child’s perspective, additional perspectives could also be gained from anyone else who might be closely involved, such as school teacher.

The spider diagram is a useful and striking visualisation of a child’s progress. The same format could be adapted to show the progress of different user groups and for different outcomes. It can also be used for groups as well as individuals. For example, at SACCS the progress of different cohorts of children has been tracked using the average scores for each of the groups. This can give a clear picture of a group's overall progress and differences between groups. For instance, to highlight whether equality outcomes are being achieved between different gender, age and ethnic groups. The assessment format has a subjective element and further research is necessary to determine whether it provides a reliable indicator of recovery. SACCS have also begun a study looking at the long-term outcomes for children and young people following their placement. A longitudinal study is necessary to determine whether there are discernable correlations between progress identified during the treatment process and the achievement of outcomes in the long term.

* Note: SACCS is the registered company name. When the organisation began in 1987 SACCS stood for Sexual Abuse Child Consultancy Service. The company now delivers recovery for traumatized children through a wider range of services and is simply known as SACCS.

References

Cant, D. (2002) Joined up Psychotherapy: The Place of Individual Psychotherapy in Residential Therapeutic Provision for Children, in, Journal of Child Psychotherapy 28, 3, 267-281

DfES (2004) Every Child Matters: Change for Children

Dockar-Drysdale, B. (1993) – Consultation in Child Care, in Therapy and Consultation in Child Care, London: Free Association Books

Johnston, C. and Gowers, S. (2005) ‘Routine Outcome Measurement: A Survey of UK Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services’ in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Vol. 10, No 3, 133-139

Mooney, C.G., (2000) Theories of Childhood: An Introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget and Vygotsky, Redleaf Press: St. Paul, Minnesota

Oxford Pocket Dictionary (1992). New York: Oxford University Press

Perry, B.D. and Szalavitz, M. (2006) – The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog, New York: Basic Books

Pughe and Philpot (2006) Living Alongside a Child’s Recovery: Therapeutic Parenting with Traumatized Children, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Solomon, J. and George, C.C. (Eds.) (1999) Attachment Disorganisation, New York: Guildhall Press

Thompson, N. (2000) – Theory and Practice in Human Services, Maidenhead: Open University Press

Tomlinson, P. and Philpot, T. (2007) A Child’s Journey to Recovery: Assessment and Planning in Work with Traumatized Children, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Walsh, M. and Tomlinson, P. (Eds.) (2006) The SACCS Recovery Programme – Unpublished Document, © SACCS Ltd

Ward, A. (2004), Assessing and Meeting Children’s Emotional Needs, Lecture notes presented at the Therapeutic Childcare Study Day, University of Reading.

Ward, H., Holmes, L., Soper, J. and Olsen, R (2004) Costs and Consequences of Different Types of Child Care Provision, Loughborough: Centre for Child and Family Research

Willis, M. (2001) ‘Outcomes in Social Care: Conceptual Confusion and Practical Impossibility?’ in Leadership for Social Care Outcomes Module Handbook 2005. University of Birmingham: INLOGOV

Winnicott, D.W. (1962) Ego Integration in Child Development, in, Winnicott, D.W. (1990) The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment, London and New York: Karnac Books

Woods, J. (2003) – Boys Who Have Abused: Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy with Victim/ Perpetrators of Sexual Abuse, London and New York: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Files

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting