BREAK, BROKEN, BREAKDOWN, BREAKTHROUGH: MEANING AND COMPLEXITY - PATRICK TOMLINSON (2023, Revised 2026)

Date added: 25/01/26

Download a Free PDF of this Article

Introduction

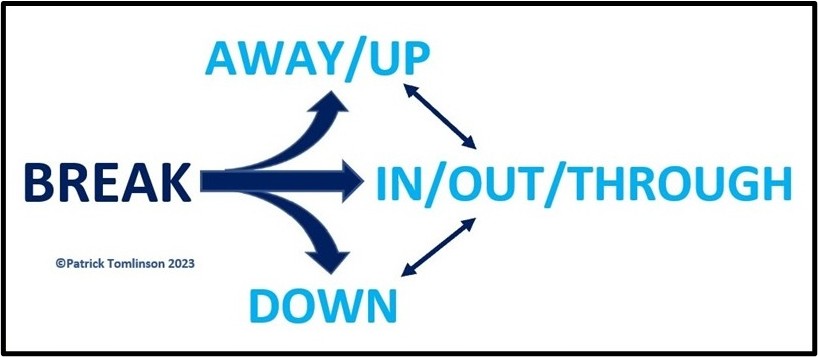

The word 'break' and its derivatives are some of the more evocative words in the English language. They can elicit a powerful response from deep within ourselves and are especially significant for professions, such as mine, that are concerned with human services systems, complex trauma, repair and recovery. In this kind of work, these words take on another layer of meaning. This article considers the complexity of such terms as break, breakdown, break-up, break-away, break-in, break-out, and breakthrough. How we use and think about these terms can have a profound effect on our lives and work. Often, they are used without much thought and with assumptions that can be unhelpful. This article aims to consider some of the meanings of the words and terms, and the dynamic relationship between them.

Break and Broken

The word break is commonly used to mean something snapping or becoming damaged under pressure. For example, the piece of wood snapped and broke. A broken bone or a fracture. Interestingly, being broke can also mean having no money. If someone says I am ‘broke’ that is usually what it means but it could also mean being broken emotionally. Break and especially broken tend to be viewed negatively. The word broken can be especially powerful and evocative, as in a broken heart, or broken-hearted; little is more poignant in the history of the arts and the depiction of human nature. However, it might also lead us to wonder what can be done to mend and repair what is broken.

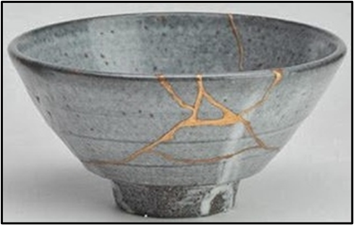

Repairing and mending are vitally important to being human and provide meaning. They are less finite than fixing something. They suggest something ongoing rather than finished. This reminds me of the Japanese concept of Kintsugi - making something more beautiful by repairing what is broken. Our aim in life should not be an unbroken perfection but making the most out of imperfection. Kintsugi dates to the 15th century and means, “to join with gold”. It helps us to celebrate and accept our flaws. When something has been damaged, it has a history, and the repair can add beauty and strength.

Repairing and mending are vitally important to being human and provide meaning. They are less finite than fixing something. They suggest something ongoing rather than finished. This reminds me of the Japanese concept of Kintsugi - making something more beautiful by repairing what is broken. Our aim in life should not be an unbroken perfection but making the most out of imperfection. Kintsugi dates to the 15th century and means, “to join with gold”. It helps us to celebrate and accept our flaws. When something has been damaged, it has a history, and the repair can add beauty and strength.

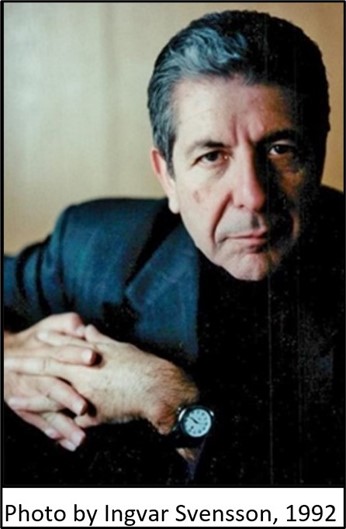

This idea of a broken or cracked vessel resonates with the lyric by Leonard Cohen,

This idea of a broken or cracked vessel resonates with the lyric by Leonard Cohen,

"There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in."

Talking about this line in his song Anthem, Cohen (in Werber, 2016) said the situation “… does not admit of solution of perfection. The thing is imperfect… And worse, there is a crack in everything that you can put together: Physical objects, mental objects, constructions of any kind. But that’s where the light gets in, and that’s where the resurrection is and that’s where the return, that’s where the repentance is. It is with the confrontation, with the brokenness of things.”

The word broken is often used to imply a highly negative situation. Such as, a system is broken. The system may be political, educational, health, legal, family, etc. Sometimes when this is said it is not clear when the system was ever complete or working. There may never have been a time when it was whole and working in the ideal, impossibly perfect way. Rather than be fixed or broken all systems tend to be in a constant state of change and evolution. So, being broken may be part of a process. I have heard people say that in the UK, for example, the education system is broken. My experience of school 40—50 years ago tells me that what is going on today is no more or less broken than it was then. It is different. We must continuously work to improve. Sometimes we might go backwards but I think language like broken is often melodramatic and unhelpful.

The word break is also often used to mean a pause between things, a break in the day, a break at work, or a break like a holiday. A short break, a long break, a permanent break. The break may be for negative or positive reasons. A planned break or a sudden break. Regular short breaks are usually seen as healthy and may help to prevent burnout or a breakdown. Phrases like taking a break or needing a break are part of everyday life. Interestingly, a planned break in continuity can help us to continue healthily, at work for example. The break can relieve the pressure that might be building up. If we need a break and either don’t realize this or cannot take one there is a risk that the pressure causes a physical/mental break, such as an illness or accident. This may force a break away, temporary, or permanent.

Breakdown

The use of the word down along with break can feel ambiguous and unclear. The way we use the word break may be simple but at the same time evoke other associations. For example, if we say, we are taking a break how might this be heard by someone who is preoccupied with break meaning breakdown? Breakdown and being down are often perceived negatively. However, it can be healthy to be down, and sometimes necessary for safety, as in to slow down. Slowing down may be good for health and well-being. On the other hand, being up can seem like being positive. There is a time for both and as is said, what goes up must come down. One young boy who had suffered huge amounts of trauma and loss stated,

I don’t need cheering up, I need cheering down.

He was tired of people telling him to cheer up - he needed to feel the depressing, sad, and painful things that had happened to him. He also needed adults to be with him while he felt his pain. As Black (1989) said,

One needs to walk through the pain, not over it, not around it.

This can be difficult for adults whatever their role. And they may also find there isn't enough attention to their difficult feelings. We must get a balance - if difficult feelings cannot be felt, acknowledged, and thought about together - what happens to them? where do they go? Being able to feel down and stay with the feeling is a developmental achievement and essential for mature health, referred to as the depressive position (Melanie Klein). Trauma can be considered in general as a break. Winnicott (1963a, p.97) described trauma in early infancy as a reaction,

… to unreliability in the infant-care process constitutes a trauma, each reaction being an interruption of the infant’s ‘going-on-being’ and a rupture of the infant’s self.

The same could be applied to trauma at any point in life – as something which interrupts a person’s going on being. When we experience a trauma, in this sense, what we need is to be understood in a way that helps us integrate the traumatic experience. For example, an infant who is experiencing trauma in the way Winnicott describes needs to be met by a responsive caregiver. This enables the infant to feel emotionally and physically held. Whatever it was that felt unbearable has been felt by another who has transformed the experience into something survivable and possible to make sense of. When a traumatic situation is not responded to in this way and either ignored or reacted to, it cannot be integrated as an experience but remains fragmented and split off.

When another similar situation arises along with an increased fear of not being understood, the new situation has the potential to be integrated along with the split-off fragments that are associated with it. This may be a reason why traumatic issues are recreated. It may be a search for the integration and potential transformation of previous fragmented, unintegrated, and split-off experiences. When trauma is repeatedly not met with a holding and containing response - the fragmented, unintegrated, and split-off experiences accumulate. This is when someone might become traumatized.

Breakdown conjures up fear of something awful. Such as a mental breakdown. Or, a breakdown of functioning, something not working. Like a broken-down car which needs a breakdown recovery service. No one ever says they need a breakdown, though the consequences can be life-changing in a positive way. For example, a ‘mental breakdown’ is a crisis, and a crisis is an opportunity. The ancient Greek word 'krisis' means to distinguish, to choose, to decide. Crisis, the Latin derivative meant a turning point in a disease. The breakdown or crisis may be a necessary part of change and growth. It is not necessarily a failure, and it might be that not being able to have a breakdown or crisis is a worse situation. Fosha (2003) describes the therapeutic potential that a crisis presents,

Crisis disrupts defenses; in this case, the crisis unraveled the organization of the preoccupied state only to reveal the underlying tendencies toward attachment disorganization. But because it disrupts defenses, crisis can be a major transformational opportunity (Lindemann, 1944), if the individual is supported through it.

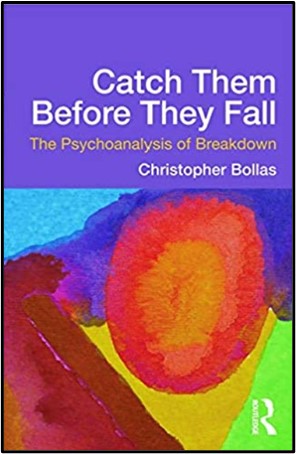

While a crisis may be an opportunity, we should not underestimate the potentially devastating consequences. In his book, Catch them Before they Fall: The Psychoanalysis of Breakdown, the pioneering psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas (2013) wrote about the transformative potential of working through a breakdown situation. A description at the beginning of the book, says,

“He (Bollas) suggests that the unconscious purpose of breakdown is to present the self to the other for transformative understanding; to have its core distress met and understood directly. If caught in time, a breakdown can become a ‘breakthrough’. It is an event imbued with the most profound personal significance, but it requires deep understanding if its meaning is to be released to its transformative potential.”

Bollas (p.5) states the consequences when a breakdown is not met effectively,

The outcome of a breakdown is not necessarily a descent into psychotic decompensation, although this may occur. More commonly, people who suffer a breakdown, which is not transformed at the time into a breakthrough, become what I term broken selves. They then function in significantly diminished ways for the remainder of their lives.

Bollas (p.16) describes some of the characteristics of being broken,

"A broken person is characteristically indifferent to their life. They are passive and resigned to their situation… Their indifference may be accompanied by unrealistic plans—writing a novel, becoming an entrepreneur—but no actions are taken towards accomplishment in their field of dreams. Instead, these plans function as projections of the broken self: broken dreams that exemplify the impossibility of success… The broken person’s affect is significantly reduced. They rarely show emotion and are not driven to anger, anxiety or euphoria by events in life. Instead, they maintain a steady remove from affective shifts; nothing is worth the effort."

"A broken person is characteristically indifferent to their life. They are passive and resigned to their situation… Their indifference may be accompanied by unrealistic plans—writing a novel, becoming an entrepreneur—but no actions are taken towards accomplishment in their field of dreams. Instead, these plans function as projections of the broken self: broken dreams that exemplify the impossibility of success… The broken person’s affect is significantly reduced. They rarely show emotion and are not driven to anger, anxiety or euphoria by events in life. Instead, they maintain a steady remove from affective shifts; nothing is worth the effort."

As Pascal and Vernon (2022) state, there is hope,

"… if we can find a container that enables, as Donald Winnicott the British psychotherapist rather wonderfully put it enables you to go to pieces without falling apart then there might be a breakthrough on the other side of that. But you've got to be able to have space for what can feel combative, what can feel aggressive, what can feel even destructive or desperate in a moment."

Fear of Breakdown and the Breakdown that can’t be Experienced

The idea of breakdown can naturally evoke fear. The extent of being out of control, suffering pain, and potentially awful consequences are real. Fear of breakdown may also be connected to a breakdown that has already happened but not consciously remembered. This fear may be held in the body and experienced physically, through anxiety, panic, pain, and other sensations and symptoms. Sometimes, these feelings may be managed by shutting off from feeling, with the consequence of being disconnected from one’s body and feeling deadened (Ogden, 2021). Bessel van der Kolk (2014) summarizes this well with his book title, “The Body Keeps the Score”. He acknowledges the long history in the field of psychology, of understanding the link between body and mind. He states,

The names of some of the greatest pioneers in neurology and psychiatry, such as Jean-Martin Charcot, Pierre Janet, and Sigmund Freud, are associated with the discovery that trauma is at the root of hysteria, particularly the trauma of childhood sexual abuse. These early researchers referred to traumatic memories as “pathogenic secrets” or “mental parasites”, because as much as the sufferers wanted to forget whatever had happened, their memories kept forcing themselves into consciousness, trapping them in an ever-renewing present of existential horror.

Joyce McDougall built upon this early work with her ground-breaking book, “Theaters of The Body: A Psychoanalytic Approach to Psychosomatic Illness”. She (1989, p.28) points out that,

The body, like the mind, is subject to the repetition compulsion.

The understanding of the body-mind connection has developed further through the work of Pat Ogden among others, who have developed a sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy and the healing of trauma. Ogden (2021) claims that,

Hope lives in the movement vocabulary of the body.

In this context, the fear felt may also be a way of keeping the memory alive so that it may become integrated. Hope and fear may be part of the same situation. In, “The Experience of Breakdown and the Breakdown that can’t be Experienced: Implications for Work with Traumatised Children”, Tomlinson (2008, p.15) argues,

The concept of breakdown is often perceived negatively, and this can dominate our response. However, with an informed approach, a breakdown can be seen as an opportunity for growth and a point of healing.

In this paper, I highlighted some of Donald Winnicott’s (paediatrician and child psychoanalyst) thinking about breakdowns and the theme in the lives of traumatised children. As well as breakdowns in their family life these children are often placed in care situations which go on to breakdown and lead to many moves which continuously reinforce a negative pattern of breakdown. Tomlinson (2008, p.15-16) states,

From my experience of working in therapeutic residential settings for traumatised children, who have suffered emotional, sexual and physical abuse, it can be safely said that by the time these children arrive in such a place, they will have experienced multiple placement breakdowns. These breakdowns are often catastrophic in nature and prolific in their frequency.

These very real and tangible breakdowns are hugely damaging and extremely difficult to recover from. What can be even more difficult to recover from are the less tangible breakdowns, of which there is no conscious memory, but which are stored in the body like a haunting reminder of something awful, which is felt but not known. Two of Winnicott’s papers are especially helpful, ‘Fear of Breakdown’ (1963) and ‘The Psychology of Madness’ (1965). He explains (1963) that if someone had a breakdown early in childhood but was unable to experience and integrate it into their history – he may seek the breakdown that has already happened in the present so that it can be experienced, survived, understood, and integrated. It will then become a conscious memory. Feeling the breakdown that cannot be remembered is most unbearable and what the person seeks relief from. Winnicott (1963, p.92) refers to these feelings as primitive agonies and he says,

The only way to ‘’remember’’ in this case is for the patient to experience this past thing for the first time in the present, that is to say, in the transference. This past and future thing then becomes a matter of the here and now, and becomes experienced by the patient for the first time.

The way the search for a contained and transformational experience of a breakdown manifests itself can take different forms. Such as a fear of death, a breakdown in health, a breakdown in the environment, and a relational breakdown. Winnicott says, for example, that a fear of death may be a compulsion to look for the death that has already happened. He states (1963, p.91),

In other words, the patient must go on looking for the past detail which is not yet experienced. This search takes the form of a looking for this detail in the future.

The breakdown cannot be let go of and put into the past until it is experienced and managed in the present. If those involved in a breakdown situation can safely survive, this could be the most important turning point in the life of the person having the breakdown. In this type of situation, it can be argued that the experience of breakdown is needed as part of recovery. However, helping someone through this can be testing to the extreme. The person who is compulsively looking for a breakdown is also terrified of it at the same time. And when there is nothing conscious to link this to it can feel bewildering and ‘mad’ to the point of seeming impossible and unbearable. This must be close to what the person felt at the time of the original breakdown. If this all works out well the breakdown may be a turning point that feels like a breakthrough. Explaining this approach in the context of therapeutic work with children and young people who had suffered developmental trauma, Tomlinson (2004, p.137), said,

“Therapeutic work with traumatized children will involve work on what is absent, missing and lost. For example, the absent parent or the move away from home, or in some cases many moves from many homes. Whenever there is an experience of absence or a break in our work with traumatized children, we can expect to work with it in terms of the here and now, as well as in the context of the past. Therefore, absences and breaks provide difficulties to work through in the present, which are compounded by the child’s past. This can make absences and breaks seem like an unhelpful disruption to treatment. However, as trauma is often associated with absences and breaks, working through these issues with the child is part of the recovery from trauma.”

“Therapeutic work with traumatized children will involve work on what is absent, missing and lost. For example, the absent parent or the move away from home, or in some cases many moves from many homes. Whenever there is an experience of absence or a break in our work with traumatized children, we can expect to work with it in terms of the here and now, as well as in the context of the past. Therefore, absences and breaks provide difficulties to work through in the present, which are compounded by the child’s past. This can make absences and breaks seem like an unhelpful disruption to treatment. However, as trauma is often associated with absences and breaks, working through these issues with the child is part of the recovery from trauma.”

Break-ups, Breakaways, Break-ins, Break-outs, Breakthroughs, and Boundaries

The term break-up is often used in a relational context but can also be used in other ways. For example, the break-up of the Soviet Union, or the breaking up of a negative pattern. It can imply that something whole is broken into pieces. It implies separating something into parts. A break-up may be neither negative nor positive but a different and new situation. The break-up may be a point of growth. Not always an endpoint but the beginning of something new. It may also be temporary and what is broken up may be made up again. A break-up may lead to a breakdown, breakthrough or vice-versa. A breakaway may help prevent a break-up by providing space in a difficult situation. A breakaway seems less definite than a break-up. People often return after a break away.

Similarly with break-ins. It is usually a negative term, as in a burglary. A violent, forced, and delinquent entry. However, it can also have relatively neutral meanings, such as breaking-in a new pair of shoes, or positive meanings like a break into a new market. Or breaking into something difficult to get into. Like making progress by breaking into a closed system. Breaking in can mean disrupting a norm. In this sense, breaking in is like breaking through.

The word breakthrough usually has a positive meaning. For example, a breakthrough in science, or a breakthrough in overcoming a big obstacle or challenge. A breakthrough may come after a prolonged period of hard work and is often admired. On the other hand, it may happen by getting a ‘lucky break’. A breakthrough suggests a radical change. Pascal and Vernon (2022), explain how a breakdown may disrupt homeostasis and through a supported transition, lead to a richer new situation. While it may seem positive, there may be unexpected consequences of the breakthrough. For various reasons, progress may be resisted and attacked. Time is needed for the change to be processed. The change also involves the loss or adaptation of previously held ideas and beliefs.

The impact of the change may lead to negative reactions, which could undermine or setback the breakthrough. In therapeutic work, the term negative therapeutic reaction is used to describe how what seems initially positive can lead to a negative reaction (Barake and Ferro, 1992). For example, this is too good to be true, so I better ruin it before someone else takes it away, and I don’t deserve this. If sudden progress is made, the unfamiliarity of the new situation and uncertainty of the future may cause anxiety and potentially worrying possibilities. I have known young people who have made progress in recovering from trauma to suddenly revert to earlier negative behaviour. Some have been able to say, they felt they would have to leave and move on if they got better. Progress may also mean more responsibility, freedom, and choice, which all have their difficulties. In other words, a potential consequence of progress can be fear.

Break-out may seem to be the opposite of break-in but the reality can be more complex. Like a break-in, a break-out can also be a forceful and delinquent transgression of a boundary. For example, criminals may break out of prison. Wars, hostilities, and riots are said to break out. And when they do the effect can be contagious. Break-out can also be used to describe a break-out of an illness, like a contagion or a break-out of acne. These examples also evoke something about a boundary being broken or fragile.

The term can also be used to mean separation and differentiation, for example, to break out of a mould or to break out of a large group into a small group. Again, there is an issue of boundaries. It could be argued that many of the issues connected to break and the related terms are strongly connected to boundary issues. Too permeable or fragile boundaries and too rigid boundaries may provoke, some of the dynamics I have discussed. In her seminal book, Trauma and Recovery, Herman (1992) discusses how boundary violations are common in the histories of patients who seek therapy because of mental illnesses. She also makes it clear how further boundary violations are always a risk in the therapeutic process. This can be thought of partly as trauma reenactment. Referring to the difficulty of the work and what is needed, she says (p.147),

The term can also be used to mean separation and differentiation, for example, to break out of a mould or to break out of a large group into a small group. Again, there is an issue of boundaries. It could be argued that many of the issues connected to break and the related terms are strongly connected to boundary issues. Too permeable or fragile boundaries and too rigid boundaries may provoke, some of the dynamics I have discussed. In her seminal book, Trauma and Recovery, Herman (1992) discusses how boundary violations are common in the histories of patients who seek therapy because of mental illnesses. She also makes it clear how further boundary violations are always a risk in the therapeutic process. This can be thought of partly as trauma reenactment. Referring to the difficulty of the work and what is needed, she says (p.147),

Traumatic transference and countertransference reactions are inevitable. Inevitably, too, these reactions interfere with the development of a good working relationship. Certain protections are required for the safety of both participants. The two most important guarantees of safety are the goals, rules, and boundaries of the therapy contract and the support system of the therapist.

She adds (p.149),

Careful attention to the boundaries of the therapeutic relationship provides the best protection against excessive, unmanageable transference and countertransference reactions. Secure boundaries create a safe arena where the work of recovery can proceed. The therapist agrees to be available to the patient within limits that are clear, reasonable, and tolerable for both. The boundaries of therapy exist for the benefit and protection of both parties and are based upon a recognition of both the therapist’s and the patient’s legitimate needs.

The same principles apply to any breakdown and to anyone who is trying to assist with such a difficult situation. As Herman says, attention must be paid to the legitimate needs of all who are involved.

Conclusion

The terms I have discussed tend to evoke assumptions. These assumptions may differ and be personal. For instance, we may always tend to be fearful of breakdowns and hopeful about breakthroughs. However, it may be helpful to keep an open mind and see the positive and negative possibilities in both as well, as in the other terms described here. Rather than being separate the terms discussed here are often interrelated. The relationship is dynamic and fluid rather than linear and fixed. If we keep this in mind we might reap the potential for repair, healing, and growth involved in these challenging processes.

Comments and Acknowledgements Before writing this article, I shared an early version of the Break diagram and asked for feedback. The authors below have kindly agreed for me to share their comments, which I think add greatly to the article. I especially find the questions they ask to be thought-provoking. I would also like to thank Dr. John Gibson and John Whitwell for their helpful comments which helped me elaborate on the diagram.

Helena Moore – Psychotherapist and Director of Practice at MASP, Victoria, Australia

(I also shared an early draft of the article with Helena)

This is a lovely metaphor. The comments you go on to make about systems repair remind me of our conversations about affecting organisational change – too much “comfort” prevents necessary growth. Of course, Winnicott would say that a good parent will be imperfect and that human beings (both parent and child) need the right amount of challenge to progress.

Today I was working with a man in his forties who recently became homeless. After 6 years of living as a recluse with a fear of going out, he stopped paying his rent and was evicted. As we explored his options, he told me that he had felt “trapped” by his abusive parents as a child. In speaking about it, he gradually came to feel some sense of pride (I think), in getting on “out in the world”. Is this an example of “seeking the breakdown that cannot be remembered”?

Furthermore, once he “remembered” he was able to accept the support that he had up until now stubbornly refused. A very interesting connection! One that I had not thought of until I read this article.

I think about the sensory body here too – a “breakthrough” must be “felt” and integrated, this takes time. I am thinking of Pat Ogden’s work where she talks about traumatic “wounding” – (I also often think of Esther Bick’s work on psychic skin).

Drew Garner – Senior Leader of Health Care Services, Queensland, Australia

The word breakdown to me implies something finite. Which it’s not. Just my feelings on it.

It is interesting to consider what these words might mean. Language is so powerful as we all know. It sets the tone for what is to come. If you’re trying to capture the opportunity, then maybe the whole process needs to be thought about. With breakdown really what’s taking place is a system being overwhelmed, unravelling faster than we can process.

Jane Keenan - Author & Provider of Professional Development, London, UK

In this context - the image - I associate ‘break’ with ‘fracture’.

In work with children in care, a breakdown has been considered bad, and a breakthrough has been considered good, but I’m not comfortable with either… something too brittle about each, or too definitive… something has been broken… did something need to be broken to achieve breakthrough…? Too splitting. I haven’t reflected on and examined these terms, but feel there are better options for a notion of a positive ‘breakthrough’… growth, penny-dropping, resolution, realisation, shift…?

And breakdown used to describe an unplanned ending… also too simplistic, and too definitive… not recognising of the breadth and depth of why an ending might come about, and does an ending have to mean irrevocably broken?

Sean Williams - Director at Birch Insights, Worcester, UK

I also associate the link between break as in break time and recreation - re-creation. I sense that links with your diagram - coming into parts/fragments/realisation/transition/(break-up breakdown) support a change/development/transformation. (Break-in/breakthrough) life is a constant flow of experience and meaning and we can get stuck in cycles/patterns/eddies that we need to be released from. Courage is key, I think.

Re break-in… We do seem to ‘relate’ from closed boundary survivor roles that may require a dissolving, breaking into and out of for life to progress and be experienced anew. Perhaps there are many roles or layers, or neural networks that protect us. So, there is a constant sense of ‘undoing’ and ‘remaking’ ourselves concerning who we were, who we are, and who we can be in the widest range of contexts.

…

A few thoughts to add - not in any expert way - just playfully integrating various ideas.

I am currently very curious about how the states outlined in the polyvagal theory relate to break down/through/in/up/away…

Dorsal vagus activation - shut down, dark gloomy helpless, shamed, foggy - perhaps a state of breakdown to be broken into (by another) or out of? Sometimes protective shells need to be cracked open with help? Maybe? Does moving through this dorsal vagal state into Sympathetic activation - fight or flight and the associated energy that brings possibility lead to a sense of break up and breakthrough/ break in/ break away?

From here we could fall back into dorsal vagus activation again - a breakdown ( down the hierarchy) or continue to move up the hierarchy and on into the possibilities that go with the social engagement system and all its colours and connections to life - passion, energy, experience and exploration, flow, free. A break-in and breakthrough?

As the Polyvagal Theory is hierarchical - and explains that our nervous system is primed for protection (defences against connection) or connection (open engaged, safe, alert) I wonder if the words and metaphors and representations in psychoanalysis relate intuitively to these three (and some blend of the three) neurological states? Up and down, in through and out?

Exciting and interesting discoveries I sense… Our flexibility, neurological and psychological is said to be our ability to cycle through these states and is seen as a sign of health (resilience?)

Is this what we are trying to do in our relational work with children who are ‘stuck’ (need help to break out of or into unfamiliar neurological states) in ventral vagal, sympathetic or dorsal vagus (shutdown) states? Places where we get stuck and repeat - no new information in-nor out from here.

Do we as practitioners use our nervous systems to titrate, lead, follow, and partner a child in and out, through and away from these defensive states so that they can take on and take in the capacity to experience all of these states whilst remaining anchored enough in the grounded and centred space that love, nurture, care, play - secure attachment - brings.

Wonderful to share ideas like this…

References

Barake, F. and Ferro, A. (1992) Negative Therapeutic Reactions and Microfractures in Analytic Communication, in, Momigliano, L.N. and Robutti, A. (Eds) (1992) Shared Experience: The Psychoanalytic Dialogue, London and New York: Karnac Books

Black, C. (1989) It’s Never too Late to have a Happy Childhood New York: Ballantine Books

Bollas, C. (2013) Catch them Before they Fall: The Psychoanalysis of Breakdown, London and New York: Routledge

Breuer, J. and Freud, S. (1893-95) Studies on hysteria, in, Standard Edition, Volume 2, London: Hogarth Press, 1955

Fosha, D. (2003) Dyadic Regulation and Experiential Work with Emotion and Relatedness in Trauma and Disorganized Attachment, in, Solomon, M.F. and Siegel, D. (Eds.) Healing Trauma: Attachment, Trauma, the Brain, and the Mind, pp. 221-281, New York: Norton

Herman, J.L. (1992) Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence, From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, New York: Basic Books

Lindemann, E. (1944) Symptomatology and Management of Acute Grief, in American Journal of Psychiatry, 101, p.141-148

McDougall, J. (1989) Theaters of the Body: A Psychoanalytic Approach to Psychosomatic Illness, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company

Ogden, P. (2021) How your Body Helps with Trauma Resolution: Interview by Timothy Hayes with Dr. Pat Ogden, in, Journey’s Dream, podcast

Pascal, L. and Vernon, M. (2022) It's Time for a Spiritual Renaissance. But what does that mean?, Perspectiva, youtube video. This dialogue focussed mostly on chapter 14 of that book by co-editor Layman Pascal: The Metamodern Spirit: Approaching Transformative Integration in Psyches and Societies

Tomlinson, P. (2004) Therapeutic Approaches in Work with Traumatized Children and Young People: Theory and Practice, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Tomlinson, P. (2008) The Experience of Breakdown and the Breakdown that Can’t be Experienced: Implications for Work with Traumatised Children, in, The Journal of Social Work Practice, Vol.22, No.1, London: Routledge

Van der Kolk, B. (2014) The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma, Viking: New York

Werber, C. (2016) “There is a Crack in Everything, that’s how the Light gets in”: The Story of Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem”, in, Quartz

Winnicott, D.W. (1963) – Fear of Breakdown, in, Winnicott, D.W. (1989) – Psycho-Analytic Explorations, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

Winnicott, D.W. (1963a) Morals and Education, in, The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment, Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis: London (1972)

Winnicott, D.W. (1965) – The Psychology of Madness: A Contribution from Psycho-Analysis, in, Winnicott, D.W. (1989) – Psycho-analytic Explorations, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

Files

- Download a Free PDF of this Article

- Download a free PDF - The Experience of Breakdown and The Breakdown that can’t be Experienced

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting