COMMUNICATION, COLLABORATION, COMPLEXITY AND WORD CLOUDS - MARK WADDINGTON (2017)

Date added: 03/10/20

Introduction

I am delighted to introduce a guest blog by Mark Waddington, who is an organizational consultant based in the UK. He is researching for a PhD in collaboration and complexity. In working with Mark, I have learnt much from his perspective on issues, such as communication, collaboration, and complexity. He has provided much ‘food for thought’ and exploration.

It is well-known that communication happens at many levels. The psychologist Albert Mehrabian (1972) claimed through his research that only 7% of communication is through words, 38% through verbal affect and 55% through body language. The detail of these findings has been elaborated during the last 50 years, but the general point remains the same. The actual words we use are significant but not as much as other aspects of communication. This also means that a significant part of communication is unconscious. Much of our verbal affect and body language happens beyond our awareness. A simple exercise of listening to a recording or watching a video of oneself, can be a disturbing experience! As psychoanalysis has shown us, even the words we consciously choose are also influenced by less conscious factors. The ‘slip of the tongue’ is universally understood.

So, on the one hand, the subject of communication is well researched, as is collaboration and complexity – in groups, organizations and societies. However, what is striking is how much, despite the vast research we tend to not pay enough attention, individually and collectively. Maybe, sometimes it is too challenging and potentially painful. Awareness leads to change, and human change is usually a slow process. The study of language can be revealing of what is happening, in ways we are often unaware of. As Mark says, it really is worth checking out what words get used and those that don’t.

Mark Waddington’s focus is on inter-agency collaboration. These relationships within and across organizations, and sometimes across communities and societies, can be full of anxieties and tensions, which easily lead to conflict. Mark provides a way of looking at what is happening in these relationships, using word clouds. The word clouds in themselves are fascinating. More importantly, they draw attention to ways in which we might improve our awareness and effectiveness, in those most challenging and complex situations.

I hope that you will find the series of articles interesting and useful – thank you Mark!

Patrick Tomlinson

The Sorites Paradox - Reflections on my first year working as a consultant in the human services.

The Sorites Paradox - Reflections on my first year working as a consultant in the human services.

The Sorites paradox, or the paradox of the heap, has been puzzling us for nearly 2500 years. It describes a scenario in which a heap of grain is repeatedly diminished, one grain at a time. When there are thousands of grains, the loss of one more does not stop us seeing a ‘heap’, but there will come a point where the heap comprises just one grain. At this point, most folk would agree there’s no heap.

The problem is that technically the same heap remains. We could sort this and define ‘heap’ at a minimum of 1000 grains, but 999 is pretty much the same. Usually, this vagueness is not a problem – we can all have different ideas about what a heap might be, and get by with a bit of common sense. However, if you ask the same question about baldness the territory starts getting trickier. Here issues of sensitivity begin to make thinking a little more complicated. The question of how many hairs might be lost before the thing called baldness happens is not just about counting – it is entangled with potentially complicated issues around appearance, identity, and age. The worldwide hair loss industry reportedly turns over more than £1.5bn pa.

By the time you arrive in the more anxious territory, such as, thinking about complex and vulnerable young people, it is much harder to be confident we understand each other or, that we might reach an agreement about what is happening or what might help. Somehow this problem of vagueness can permeate thinking in ways that paralyse progress. Anxiety can drive a frame of mind, hoping ‘somebody does something’, alongside a sense that decision-making lies elsewhere in a professional network. The vagueness allows everyone to be a little unclear about what the problem is, or indeed what should be done and by whom.

As I consider my experience, as a consultant and doctoral researcher, working with professional networks. I am struck by the stubborn persistence of vagueness. In my view, there is an alternative, which often lies in a leadership model that affirms differing and sometimes contradictory viewpoints across a group’s membership. Often this affirmation can be achieved through relatively straightforward questions and a determination to take the time to establish all views. The ensuing clarity may well bring its own discomfort, but also the prospect of collective confidence as to how the land lies.

Sorites II - Paradox or Polarisation?

Sorites II - Paradox or Polarisation?

The lovely thing about the Sorites paradox is that it tells a story that helps disagreements make sense. A group of people is likely to contain a group of viewpoints and there’s a fair chance that some will be in contradiction. The big question is whether these contradictions can be helpful. Let’s assume these people have become a group to sort out a problem, even if one contradiction might be that they do not agree exactly what the problem is. The group can deal with contradictory viewpoints in various ways.

A Polarised Position, where two or more group members with differing viewpoints behave as though their viewpoint is most compelling and compete for supremacy.

A Paradoxical Position, where contradictory viewpoints are accepted as a paradox by a group who will then puzzle together as to how best to achieve resolution.

Of course, it is also an option not to acknowledge contradictions at all. They could be Passed Over for a variety of reasons:

• Group members might be so keen to fit in that they will only display behaviours and thoughts that they imagine will be acceptable to the group.

• Membership of the group might presuppose a common viewpoint and be exclusive of differing views.

The task of the leader is to steer the group between these positions and set a course that maximises progress toward a resolution of the group’s problem. There are strengths and vulnerabilities associated with each of these positions:

A supreme group member in the Polarised Position might be experienced as Charismatic and Inspiring or as Autocratic and Repressive.

The Paradoxical Position might be experienced as inclusive and enabling, or creating a chaotic talking shop where nothing is ever decided.

The Passed Over Position provides an uncluttered environment for decision-making but also the space for miscommunication or even dysfunction that could be experienced as sabotage.

Simone Weil (1970, and in Sparrow, 2003) famously stated, "When a contradiction is impossible to resolve except by a lie, then we know that it is really a door”. Leadership is all about operationalising this statement rather than going mad!

Success in this enterprise is very much tied up with the ways in which people talk and think together. My research examines discourse in complex collaborative networks, and I believe it is possible to improve the chances of a good outcome, through observation and understanding of the ways that organizations talk to themselves and each other.

Sorites III - Doing Things Differently

My last two postings describe how when people work together, the phenomenon of vagueness generates contradictory views, and how leaders can help a group navigate these tensions.

When a contradiction is, “impossible to resolve except by a lie”, we’re describing a stuck situation where the words we have available, appear not to have the capacity to help us move on. So, when Simone Weil goes on to say, “we know that it is really a door”, she makes something clear about those words that will need to change if things are to turn out differently.

Words are the fundamental tools used when people talk and think together, though there are many other ingredients - eye-contact, intonation, speed of delivery, etc. This posting is about the words, especially in the context of organizations. It really is worth checking out what words get used within an organization, and those that don’t. My research and consultancy roles have allowed me to observe the language being used in different settings and it is striking how much it varies. Let me show you why this matters.

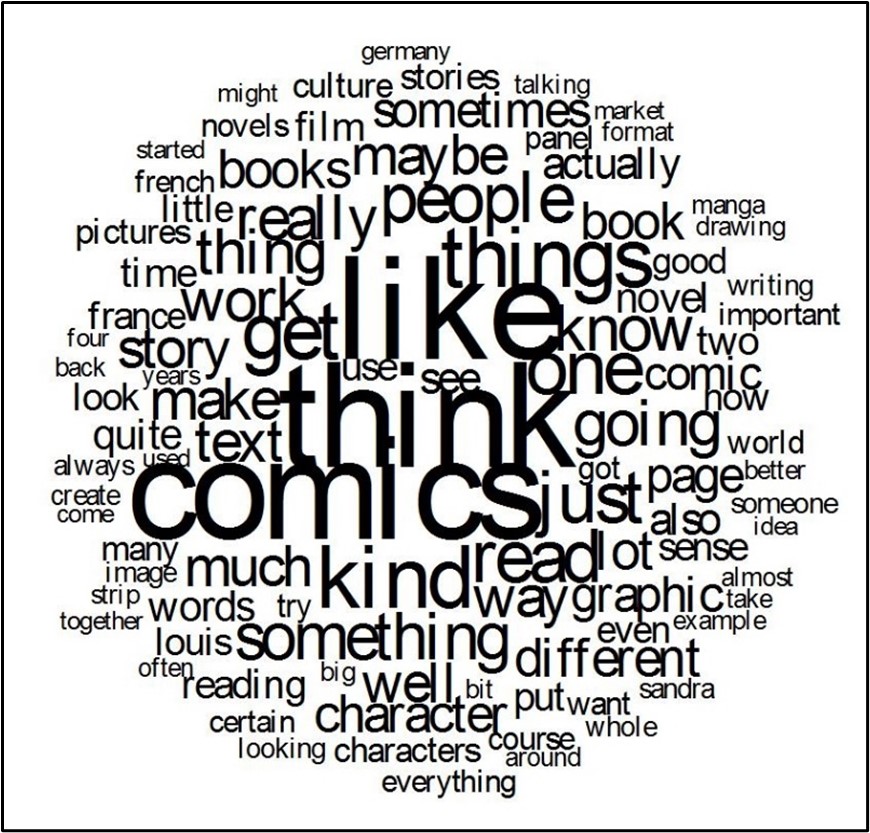

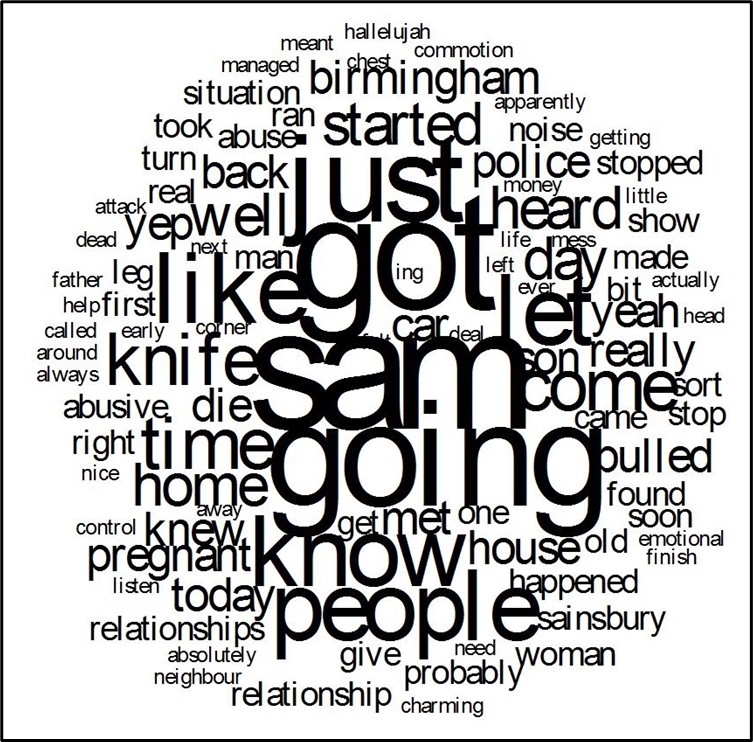

Here are two, word clouds taken from collaborative and oppositional discussions. One is a group of artists discussing graphic novels with an enthusiastic audience who are all having rather a nice time. The other is from a daytime TV tabloid talk show that has been described as “human bear-baiting”. The discussions are transcribed and then an algorithm identifies the top hundred words of three or more letters (leaving out ‘the’ and ‘and’). The more a word is used, the larger the font.

This cloud really speaks for itself. The group are thinking about comics and the word ’like’ features in two ways - one to do with enjoyment and one to do with comparison. The next frequency of use - ‘kind’ and ‘thing’ are words used to guide lines of thought. Crucially the words join people together in a collaborative task to construct something, which in this instance is a good experience.

The next cloud also speaks for itself – this really is about winding people up. Most strikingly, the word "think" is absent. The name in the middle belongs to a vulnerable witness. The human bear-baiting description was used by a judge in a legal case following a physical assault that took place during a different episode of this programme.

Imagine what life would be like if one of these clouds contained your top hundred words. The first cloud would give you the capacity to be charming, have fun, make friends; the second might well lead to a criminal conviction.

I’ve deliberately identified oppositional and collaborative discussions to illustrate how language affects thinking. The language used in most organizations will sit somewhere between these extremes and generally we have a choice of more than just a hundred words. None the less, most folk will be able to recall moments when communication headed toward one of these poles. Word clouds provide a snapshot of organizational culture in real-time. They are co-produced by everyone involved in a discussion. They can help us consider communication processes without pointing a finger of blame. This can be a helpful route to navigate the anxieties that often accompany work to enable an organization to do things differently.

William Bout www.unsplash.com

William Bout www.unsplash.com

Donald Trump, Twitter, Complexity and Brevity

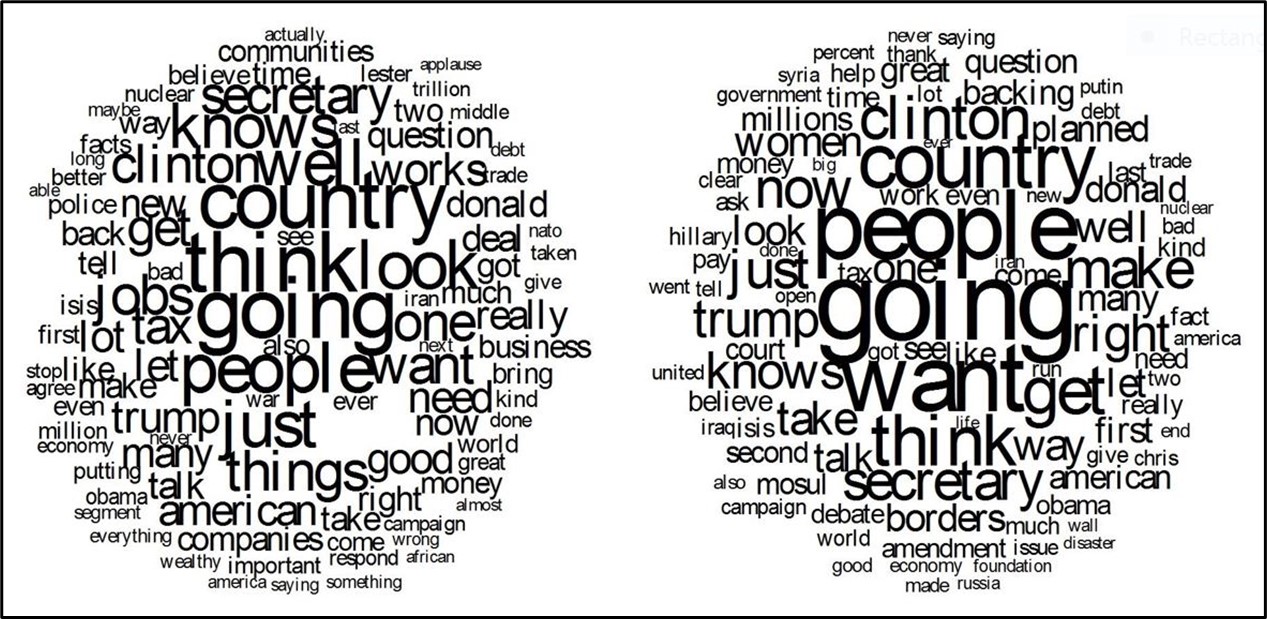

Here are word clouds from the first and third presidential debates. They show the top hundred words spoken.

I’ve deliberately made them small to focus, twitter-like, on the main words, and to show a change of tone. Crucially, while the words ‘think’ and ‘know’ reduce, the words ‘going’ and ‘want’ increase. Focus transfers from thinking and knowing, to wanting and going. The word ‘going’ is the pivotal word in the somewhat intemperate daytime TV programme, discussed previously.

As a doctoral researcher, I focus on subtleties, and the careful construction of rigorous argument to achieve an understanding of process. I am struck by how quickly these changes have happened. This contrasts with the longer time it can take to marshal data and develop rigorous argument.

Word clouds have many helpful, interesting and practical uses. They are one of a variety of methods available to examine organizational discourse. Rather helpfully, it is pretty straightforward to gather speech data and process it in this way. So, if you asked me, we could prepare one fairly quickly and potentially capture these kinds of changes.

Often, we are unaware of our own language and how the organizations we work in are changing and developing. Analysis of the words we use can provide insights into our cultures and offer ways in which we might influence them. Imagine the difference if the word ‘helping’ replaced ‘going’ on these clouds. How would that impact on politics in the USA? How would an equivalent change affect your organization? It might be profitable to consider ways in which this could be achieved.

Mark Waddington

Mark Waddington

www.mwcollaborations.com

References

Mehrabian, A. (1972) Silent Messages: Implicit Communication of Emotions and Attitudes, Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing Company

Sparrow, S. (2003) Evolution: Part of God’s Grandeur, in Comforts of Home: The Flannery O’Connor Repository, http://www.flanneryoconnor.org/ssevolution.html#ixzz4QpSxdOJC

Weil, S. (1970) First and Last Notebooks, trans Rees, R. London: OUP

Forbidden Planet Internal Blog (2006) Lost in Translation Panel Discussion Transcription,

http://www.forbiddenplanet.co.uk/blog/2006/lost-in-translation-panel-discussion-transcription/

Judge Blasts Kyle Show as Trash (2007) http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/7011962.stm

Files

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting