MODELS IN THERAPEUTIC WORK WITH TRAUMATIZED CHILDREN - PARTS 1 & 2 - PATRICK TOMLINSON (2014, REVISED 2021)

Date added: 23/03/21

Download a Free PDF (Revised 2021)

MODELS IN THERAPEUTIC WORK WITH TRAUMATIZED CHILDREN - PART 1

The term model has arisen significantly during the last decade or so, to imply a well thought through and coherent way of providing a service. Other terms that may mean something similar are framework, ethos, philosophy, and approach. I will describe how I see important principles of a Model.

Internal Working Model One of the first uses of the word model in our field of work may have been by John Bowlby (1969) who used the term ‘Internal Working Model’. This is related to the model internalized by an infant as to how the world around him works and his place in it. The model is based on the infant’s perception of his experience. For example, I am lovable/unlovable, carers are protective/harmful, and the world is safe/dangerous. It can be seen from this that the model includes the infant’s view of himself, those closest to him and the wider environment or world. The model is an internal template that the infant may not be conscious of and though it is resistant to change, it can be modified by new experiences.

Internal Working Model One of the first uses of the word model in our field of work may have been by John Bowlby (1969) who used the term ‘Internal Working Model’. This is related to the model internalized by an infant as to how the world around him works and his place in it. The model is based on the infant’s perception of his experience. For example, I am lovable/unlovable, carers are protective/harmful, and the world is safe/dangerous. It can be seen from this that the model includes the infant’s view of himself, those closest to him and the wider environment or world. The model is an internal template that the infant may not be conscious of and though it is resistant to change, it can be modified by new experiences.

As with parenting, the outcomes of services for traumatized children are going to be determined by,

• the quality of the relationships between the child and those closest to him (parent/carer/therapist).

• the immediate context and quality of relationship (extended family/organization – culture, leaders, managers, and supervisors)

• the local community; and the wider socio-political-economic environment.

Development Takes Place in an Ecological System While trauma may often be perceived as an issue between the ‘victim’ and ‘perpetrator’ it is not helpful to ignore the context or ecological aspect. Trauma happens within an environment, such as a home, a family, a neighborhood, a community, and a society. A model for recovery needs to consider not only the various levels of the context but also the relationship between them. For instance, it would not be helpful to create a model, however rational it might seem in its clinical approach if it conflicts with cultural values and norms. Supporters of the ‘ecological model’ rightfully argue that outcomes can improve by intervening at any level of the context. For example, positive outcomes for children might be achieved by improving the support provided to primary caregivers, and/or reducing poverty will also help.

If we are going to influence and change a child’s 'model' it makes sense that the approach must also involve, working directly with the child’s internal and external worlds. This will include all of those who work with and look after him as well as the context within which everything happens. Most importantly these different elements must be integrated. As James Anglin (2002), the Canadian researcher on residential care has said, they must be ‘congruent in the best interests of the child’.

While most people might not think consciously in terms of models, in essence, it is as Bowlby described, the way we make sense of the world around us and our part in it. For example - what do I want to achieve; what are my ideas of the methods I might use to achieve it; what evidence do I have about the effectiveness of the methods; and what are the outcomes; including unintended outcomes or side-effects?

The Need for a Clear Model When we are a team providing a service, we must have a shared model that we work to. Without this, the service is likely to be fragmented, inconsistent, and potentially conflict-ridden. In working with traumatized children, this is not helpful. Rather than provide children with important levels of consistency and predictability that are necessary for their recovery, the service is more likely to resemble the environments in which they were traumatized.

When I began my career in 1985 at an English therapeutic community (Cotswold Community), the organization had a very well-developed model. It was not referred to as a model, but a therapeutic approach. The most striking feature for me was that the organizational aspects were fully incorporated into the model. Leadership, role clarity, authority, management, structure, and boundary management were seen to be equally important to the ‘treatment task’, as the direct therapeutic work with the children. Not only were both aspects important, but the relationship between the two was also understood to be critical. This can be thought of as the relationship between therapy and management. It can also be reflected in what people sometimes refer to as the relationship between ‘business and care’.

A Parenting Model A comparison can be made with the task of parenting. Parents of an infant strike a balance between attending to the management of the environment and focusing on the infant’s emotional/physical state. Keenan (2006, p.33) referred to Winnicott’s conceptualization of these two functions that are both necessary to ‘hold’ the child,

The object-mother is the mother as the object of her infant’s desires, the one who can satisfy the baby’s needs … The environment mother is the mother in the role of ‘the person who wards off the unpredictable and who actively provides care in handling and in general management’ (Jacobs, 1995, p.49).

Sometimes the parent may become so caught up with the infant on an emotional level that other issues are neglected, like shopping, housework, paying bills, etc. At other times, the parent may be so busy with these things that the infant’s emotional cues unnoticed. Holding the two together is a challenge that ebbs and flows. Unless things become extreme in one way or another, the overall experience for the infant will be ‘good enough’.

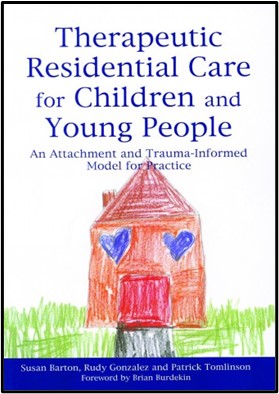

From this example, it is evident how all these aspects of the infant’s environment connect to his overall sense of well-being. It would be no use to have emotional needs met within the context of an environment that is not being well-managed. The consequences of the lack of management may lead to a deterioration that would cause stress for the parents and potential hazards in the environment, which would impact negatively on the infant. The same applies to organizations. It could be argued that effective management provides the container in which therapy can take place………..It is crucial in the residential treatment of traumatized children that the whole organization and every activity within it are aligned to this work………Confirming the importance of this, Canham (1998, p.69) argued, “...the whole way the organization functions is the basis for the possibility of an introjective identification.” The children will internalize not only the relationships they are most directly involved with but also the way the whole organization functions. (The above section has been adapted from Barton et al., 2012, p.47)

From this example, it is evident how all these aspects of the infant’s environment connect to his overall sense of well-being. It would be no use to have emotional needs met within the context of an environment that is not being well-managed. The consequences of the lack of management may lead to a deterioration that would cause stress for the parents and potential hazards in the environment, which would impact negatively on the infant. The same applies to organizations. It could be argued that effective management provides the container in which therapy can take place………..It is crucial in the residential treatment of traumatized children that the whole organization and every activity within it are aligned to this work………Confirming the importance of this, Canham (1998, p.69) argued, “...the whole way the organization functions is the basis for the possibility of an introjective identification.” The children will internalize not only the relationships they are most directly involved with but also the way the whole organization functions. (The above section has been adapted from Barton et al., 2012, p.47)

The Therapeutic Task The balance between the diverse needs described above and how the potential conflict is managed is a key part of the therapeutic task. Individual needs are always responded to within a context. For example, how are individual needs met within the context of group needs? We do not help children and young people by ignoring the reality of the context, which includes the resources available. We must find creative ways of meeting needs. For example, a parent with five children is going to manage things differently compared to a parent with one child. The outcomes for each child are determined by how the situation is managed – by the parents, the extended family and the child’s resourcefulness. In some cultures, the local community has a crucial role in looking after all the children. Isaac Prilleltensky (2006) argues that wellness occurs in the inter-relationship between the personal, the relational and the collective.

When I began my career, we had a team of five care workers looking after a group of ten children. Nowadays, with the same type of child, it is more likely to be a team of ten looking after a group of three. The challenging question in the face of such change is whether the core principles of a model are sustainable?

Continuous Development and Evolution Whether Darwin precisely said that quote or not, it is a critical point. Models must be alive and adaptive – they must be open systems and have feedback loops, so they can receive the information they need from all parts of the system. In other words, a model can never become a fixed entity, as one part of the system changes other parts must adapt. It must continuously evolve. For example, a change in the external environment, politically, economically, or professionally will require an adaptation. As with evolution, those that survive are the most adaptive.

Continuous Development and Evolution Whether Darwin precisely said that quote or not, it is a critical point. Models must be alive and adaptive – they must be open systems and have feedback loops, so they can receive the information they need from all parts of the system. In other words, a model can never become a fixed entity, as one part of the system changes other parts must adapt. It must continuously evolve. For example, a change in the external environment, politically, economically, or professionally will require an adaptation. As with evolution, those that survive are the most adaptive.

References

Anglin, J. (2002) Pain, Normality, and the Struggle for Congruence: Reinterpreting Residential Care for Children and Youth, New York: The Haworth Press Inc.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Loss. New York: Basic Books

Jacobs (1995) D. W. Winnicott London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage Publications

Keenan, K.A. (2006) ‘Food Glorious Food: An Exploration of the Issues of Anxiety and its Containment for Children and Adults Surrounding Food and Mealtimes in a Residential Therapeutic Setting.’ MA Dissertation, Planned Environment Therapy Trust

Prilleltensky, I. (2006) ‘Psychopolitical validity: Working with power to promote justice and wellbeing.’ Paper presented at the First International Conference of Community Psychology, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 10th June 2006.

Barton, S., Gonzalez, R. and Tomlinson, P. (2012) Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Young People: An Attachment and Trauma-informed Model for Practice, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Comments

Joanne Prendergast - Social Care Worker at St Bernard Group Homes, Ireland - Very informative critique on the aspects of well-intended child care models. The flexibility around areas that create the holding environment is crucial to this very delicate but valuable task.

Andrew Collie - Organizational Consultant, England - Thanks for this Patrick. Childcare without a model is childcare without concern for the child.

MODELS IN THERAPEUTIC WORK WITH TRAUMATIZED CHILDREN - PART 2

In part 1, I discussed how models develop in childhood as ‘internal templates’. By the time a child becomes an adult, he or she will have a way of relating to others based on their ‘internal working model’. Once a child is born the parents ideally have clear ideas about what will be good for their baby, and the capacity to provide it.

Different Versions of Parenting We all know from observing and/or being a parent that there are different versions of how to look after children. Usually, our version is based on our childhoods, what we have learnt in our families. If they have internalized a positive experience of being parented, most parents want to parent as theirs did. If they have not and they have not been able to acknowledge the difficulties, they may also parent similarly and repeat the negative experiences. This is how a cycle of deprivation and abuse continues. Or if they are more in touch with the reality of their childhood difficulties, they may wish to be different to their parents and bring up their children in a better way. However, even with all the knowledge now available, few first-time parents will have received much formal education on parenting.

Add into the equation that both parents will have had different childhood experiences and will have differences and similarities in their views on parenting. Differences may be positive when they provide their children with a wider range of positive qualities. However, too much difference in dealing with basic issues could be too contradictory, unpredictable, and unhelpful. Sometimes the parents might not be conscious of their differences until they have a baby, their child reaches a certain age, or situations arise. Each stage and event of childhood can have the powerful effect of resurfacing strong feelings in the parents, related to their childhoods, which they may not have been aware of or had repressed. On the positive side, how the parents manage their feelings, work together, and resolve differences are vital parts of parenting. It provides children with a role model on how we can positively cope with difficulties and how differences can be useful rather than harmful.

The relevance of parenting is clear when we think of therapeutic models. Whether we are working in foster care, residential care, therapy or teaching, parent-child dynamics will be involved. The task will require that the foster carer, residential carer, therapist, or teacher can reflect upon and untangle what is in the child’s best interests. One child who was living in a residential children’s home complained to me,

You can tell how each of the carers was brought up because they all have different rules and attitudes at mealtimes.

There is nothing like the way we eat together to highlight differences! In the absence of a clear and agreed model, the carers were doing their own thing based on their points of view. There could be 8-10 adults in a team, so the potential for confusion is huge. It can be hard for two parents to provide the necessary consistency for a child, so providing it among a large team is incredibly challenging.

The Need for Consistency and Predictability When there is a team working with a child it is especially helpful to have a model. Traumatized children need predictability and consistency, to help them feel safe and to stabilize their emotions. Only once this is achieved can they begin to make use of the experiences they need to recover and develop. As Perry and Szalavitz (2006, p.245) state,

I also cannot emphasize enough how important routine and repetition are to recovery. The brain changes in response to patterned, repetitive experiences: the more you repeat something, the more engrained it becomes (Perry and Szalavitz, 2006, p.245).

Without a clear model, chaos is likely to reign. For many years various reports and investigations into ‘looking after children in care’, have found that a clear ethos or philosophy, along with strong leadership are the most consistent factors in positively run organizations that have good outcomes for children and young people. What used to be termed a philosophy of care, is now more frequently referred to as a model of care. Whether we are talking about care, therapy, or teaching, having an appropriate model is essential.

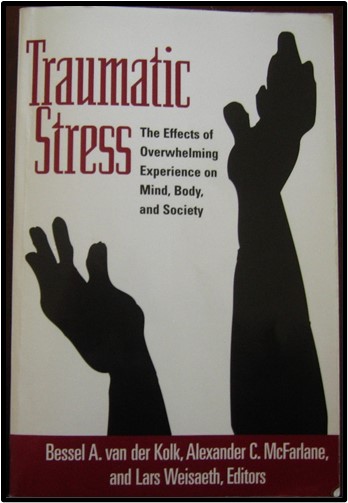

Evidence-informed Principles A model needs to be based on the best information available for the specific task. For example, if we are teaching an autistic child, the research and theoretical base will be different from that for therapy with a traumatized child. There may be overlaps but there will also be differences. I had a steep learning curve when I began work with traumatized children and another one when I moved and spent time working with children diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome. The model that worked with one did not work with the other. It can be said that in working with any child, we need to be adaptive to each child’s personality. For instance, it is now well-known that everyone has different learning styles and therefore different learning needs. But the differences between children with distinct types of complex needs are especially challenging to adapt to. Turner et al. (2007, p.537) has said that in work with complex trauma a variety of approaches are necessary and,

"Helping people who develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the after¬math of a traumatic experience is a complex process that cannot simply be described like a cookbook recipe."

"Helping people who develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the after¬math of a traumatic experience is a complex process that cannot simply be described like a cookbook recipe."

A model can provide guiding principles, standards, specific techniques, dos, and don’ts. But most importantly it should equip the people doing the work with the ability to think within a framework and work things out together. A model provides parameters within which things can be tried and monitored. What works can continue and what does not may need re-thinking or persevering with. Having a benchmark provides a point from which ideas can be critiqued. If there is not a benchmark, how do we notice how far something is drifting - a bit like walking in the fog, without even a vague marker to keep a sense of direction.

Model Fidelity and Leadership Having a good model on paper is not a guarantee of good outcomes. Other key factors will also determine success. For example, is the model embedded in the culture, is it understood and do people feel a sense of ownership. It is particularly important that a model is culturally sensitive and considers cultural values, language, and belief systems.

In working with traumatized children, as I mentioned in the previous blog, every aspect of the environment and how the various parts work together is vital. Different terms like integration, congruence, and joined-up have been used to explain the importance of this. A trauma-informed environment is necessary, and this includes everyone who is in any way involved – carers, therapists, teachers, managers, senior executives, administrators, etc. Creating this requires a cultural change because how people think about the children, the task and how they relate to each other is all relevant to the model.

Effective leadership and implementation of a model is challenging work. To fully establish a strong culture with a clear model can take at least 2-3 years, if not longer. By this, I do not just mean that a model is created on paper, but that it becomes genuinely reflected in the way that individuals and the organization work. A fully established model can be recognized by the positive qualities that run through the organization, with everyone speaking the same language. It is reflected in the consistent quality of relationships between adults and children and at all levels of the organization. Any model aims to achieve the best possible outcomes for children, so continually evaluating, learning, and adapting must be part of the culture. As I have said, a model is never finished, it is always evolving.

References

Perry, B.D. and Szalavitz, M. (2006) The Boy who was Raised as a Dog: And Other Stories from a Child Psychiatrist’s Notebook, New York: Basic Books

Turner, S.W., McFarlane, A.C. and van der Kolk, B.A. (2007) The Therapeutic Environment and New Explorations in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress, in van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A.C. and Weisaeth, L. (eds.) Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body and Society, New York: Guilford Press

Files

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting