REASONS A TRAUMATIZED CHILD RUNS AWAY? - PATRICK TOMLINSON (2015, Revised 2024)

Date added: 13/12/23

Download a Free PDF (English) of this Article

Introductory Note: I wrote this in 2015, revised it a little in 2021, and recently Maria João Braga da Cruz kindly offered to translate the article into Portuguese. Interestingly, she felt that there is no exact translation in Portuguese for how the word truant is used in parts of this article. Her comments below are helpful and interesting.

In the process of translating this article, thought was given to how best to convey the intention of using the term "truant", the literal translation of which in Portuguese would be "faltoso(a)", the one who escapes from the place where they should be, the one who misses classes, would be the most common example of its use. However, the application of the term "truant" in this article written by Patrick Tomlinson, and in the English language in general, goes beyond that.

To adjectivize a mind as "truant" is to refer to a mind that through this absence is looking for something. A good example is that of a person who is phsically present but whose mind evades being present. Ultimately, to apply the concept of "truant" is to invite us to think about the one who is absent, from a dynamic perspective that goes beyond this absence. The child or young person who is absent is evading from and towards something. Based on this premise, which explains the more complete and complex term in English, and to facilitate translation, the decision was made to replace the concept of "truant" with absent, e.g. the one whose mind is driven to absence, to being absent. (Maria João Braga da Cruz, 2024)

I have been thinking about the link between trauma and running away. Running away is also sometimes referred to as being missing, or as truancy – staying away from school without leave or good reason. It can be associated with adolescence and not necessarily an unusual occurrence. In work with traumatized children and young people, running away can be one of the most challenging and troubling themes. However, as a universal theme, it is one of the most important matters we need to find a way of thinking about and working with. We can’t just 'lock' troublesome children up or ironically ‘throw them out’ after they’ve come back from running away.

I use the quote by Willie Aames because I think it makes at least three useful points. One is that running away as with many behaviours can have different meanings beneath the surface. Secondly, Aames implies that his behaviour was a form of communication. It also seems that no-one picked up on his communication in the way he was hoping for unconsciously. Thirdly, he makes it clear that his conscious view only emerged many years later. So, as a child, he didn't know why he was running away. If he had been asked, he probably could not have given a meaningful answer. Even though the quote says that he wanted someone to run after him, this doesn't explain why he had the impulse to run. Why did the impulse develop when he was five?

For most children, there is a point in their development where they realize they can run away. This may just be a sign that the child has a healthy curiosity about what else might be out there. The child realizes she has the potential to go outside of her parent’s world. It may be a way of experimenting with crossing boundaries. To run away one must go over a line. This possibility, which is more of an interest in exploration and discovery may enter the child’s imagination and fantasies even if it isn’t acted out. Is the urge to run away a move towards independence? “Once I ran to you, now I’ll run from you”, as the lyrics to the song ‘Tainted Love’ say. Interestingly, this could apply to the natural disillusionment a child might feel towards his parents in the process of separation and individuation.

The child psychotherapist

“A truant mind has to have something to truant from and something to truant for. The adults provide something to truant from and the adolescents have to discover something to truant for. In straightforward psychoanalytic terms, adolescents truant from parents as forbidden objects of desire, as the people who have deprived them; they truant for accessible objects of desire, for the possibility of making up for the inevitable deprivations they have suffered growing up with their parents, for the sex the parents can’t provide. Truanting has something utopian about it, and not truanting something unduly stoical or defeated. The truant mind matters because it is the part of ourselves that always wants something better; and it also needs to come up against resistance to ensure that the something better is real, not merely a fantasy.”

The child might feel excited and slightly fearful about the possibilities. A traumatized child may have far more troubling connections with the impulse to run away. Trauma happens when a person is faced with a frightening situation that is impossible to escape from. The powerlessness leads to overwhelming terror, which is traumatizing (Herman, 1992). The body is unable to escape, leaving the mind and body unprotected from the full terror of what is happening. The only form of escape, especially for children who face repeated traumas such as abuse, can be to dissociate. In other words, their mind becomes removed from the body. As if it isn't happening to them. Physiological and psychological mechanisms kick in to reduce pain and increase the chance of survival. As a result, the child's body might feel useless to him. He may feel let down by his body and ashamed of his 'failure' to escape (Van der Kolk, 2014). We often see traumatized children who are lacking basic physical competence. Many have difficulties in coordination and can appear clumsy. Self-esteem deteriorates and the problem of having an incompetent body and mind grows.

As a child begins to recover from trauma, he will begin to gain confidence. He will become physically and mentally more capable. For the reasons I have mentioned, gaining a sense of physical mastery is extremely important for these children. Running might be one of those areas of mastery along with other physical activities. Their previously 'useless' bodies now begin to feel more capable. One consequence of this is that they can now experiment with escaping. If a small child has been unable to escape terrifying situations at the hands of an adult, as he grows bigger it must be liberating to be able to run away. The message might be, I am no longer powerless, and I can get away when necessary. Just the experience that it is possible might be enough. The child can't necessarily trust that there won't be a need at some point.

If a traumatized child feels empowered by being able to run away, in some ways it might be an important step forward. If this is the case, we need to be careful not to be punitive and harsh in our response.

This would be a bit like punishing a victim for giving up the victim role.

I would add that it is generally a good thing not to be punitive and harsh towards a traumatized child. This isn’t likely to induce a feeling of wanting to stay. What we do on the child’s return can be crucially important. How do we express our concern but also provide her with the space to discuss, explore and say anything that might be important? Does she feel welcomed back? How do we feel about having her back? Sometimes people may feel relieved and angry at the same time? Even if there is a healthy aspect of development in a child running away, those being run away from are not likely to welcome it. So, what are the kind of questions to consider? One well known and key question is whether the person is running away from or to something. Or as the American novelist Sherwood Anderson (2012, p.220) said, could it be both?

I would add that it is generally a good thing not to be punitive and harsh towards a traumatized child. This isn’t likely to induce a feeling of wanting to stay. What we do on the child’s return can be crucially important. How do we express our concern but also provide her with the space to discuss, explore and say anything that might be important? Does she feel welcomed back? How do we feel about having her back? Sometimes people may feel relieved and angry at the same time? Even if there is a healthy aspect of development in a child running away, those being run away from are not likely to welcome it. So, what are the kind of questions to consider? One well known and key question is whether the person is running away from or to something. Or as the American novelist Sherwood Anderson (2012, p.220) said, could it be both?

The person could be running away from something external or internal, or both. From something internal or external. From herself or someone. Running away person could be as Phillips (2009) suggests, “someone who is trying to evacuate himself from his own home because there is a war going on”. On the one hand, ‘the war’ may be internal. If the child has violent feelings running away may feel like a way of protecting herself and others from acting out those feelings. We know that fight-flight is one of the responses to threat. Flight may feel like a better response than fight. On the other hand, something may be going on in the living situation that the child is running away from. For example, is she being bullied? Is someone luring her away? Are there unsafe, frightening situations that she is either running away from or to? Does the child just feel safer, freer and in control being away from people? Is she running away from the vulnerability of forming a good relationship? Is there something positive she is running to? Such as a wish to be reunited with family. As well as missing their family, children who are removed and in care often feel worried about the welfare of their parents and siblings. Even though we might have concerns about the family situation the wish for connection is natural (Coman and Devaney, 2011, p.42).

“Children who are looked after in the care system are disproportionately likely to go missing. One in every ten looked after children will go missing compared to an estimated one in every two hundred children generally. They are also much more likely to be reported missing on multiple occasions: in 2020, over 12,000 children who were looked after went missing in over 81,000 missing incidents. Nearly 65% of missing looked after children were reported missing more than once in 2020.”

The UK Department of Education (p.4) explain that, “children in residential care are at particular risk of going missing and vulnerable to sexual and other exploitation.” They summarize the reasons for children running away, such as abuse or neglect, or to go somewhere they want to be, or through coercion. They emphasize that about 25% of children that go missing are at risk of serious harm.

A child running away can also be an exceedingly difficult experience for those who are being left behind. It can feel that the child is rejecting the care being offered. There can be a lot of worry and anxiety involved. When I started work looking after ten traumatized boys it wasn’t long before I experienced a child running away. Given the children’s lack of concern for safety and their vulnerability, the risks were significant. We were in a therapeutic community on a farm, about six miles from the nearest town. Sometimes by the time a boy who had run off got outside of the community, he would come back, already tired by his efforts! This was one advantage of the location. Running away didn't put the children in such immediate danger as it might in a city. There have been many reported instances of children in out of home care, getting involved with gangs, drugs and sexual exploitation, etc. This inevitably causes huge anxiety for the adults looking after the children. The anxiety can escalate so that all attention is on stopping the child from running away and little on thinking why she may be doing it.

We must also pay attention to our feelings and thoughts while the child is ‘missing’. What is the running away evoking in us? For example, is the child projecting some of her fears into us? Is she giving us a taste of what it feels like to be abandoned and run away from?

A colleague, Tuhinul Islam Khalil (2013) mentioned that in Bangladesh, children living in a large residential home where he worked were often running away and ‘dropping out’. Contact with the children’s mothers was not encouraged as many of them were sex workers. Tuhinul recognized that the children needed their ‘mums’. He changed the organization's policy so that,

Mum can come and visit any time they want. They don’t even need an appointment to come. So, it is like magic, within a month the dropout rate has nearly gone.

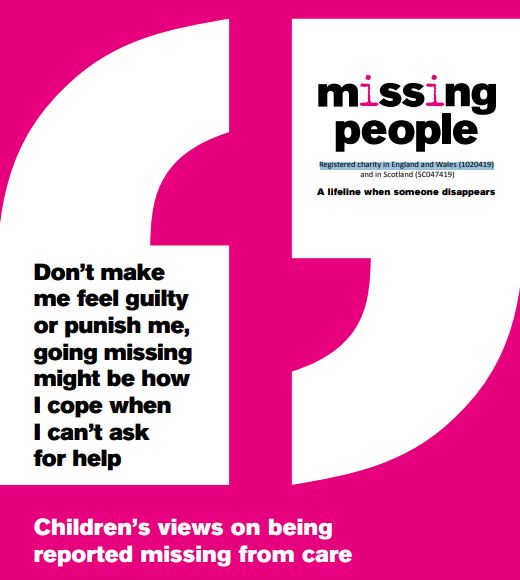

This was an excellent example of thinking about the underlying reason and meeting the need. Continuing with the theme of understanding the reasons, Missing in Care (2021, p.31) say,

The young people we consulted want carers, social workers, and the police to avoid making assumptions about them and why they might have gone missing. These professionals should try to understand their reasons, acknowledging that every child is different and will be facing different challenges.

Referencing quotes from young people, Missing in Care (p.17) states,

Everyone is different so don’t treat us all the same, we do things for different reasons, you need to know, and, … Talk to me, get to know me, don’t judge me, understand why I might go missing and help me manage those feelings and situations before it gets out of hand. Young people go missing for a reason, try to understand that. When we go don’t be angry or make us feel bad.

Interestingly, the young people consulted with are in effect saying, think about the meaning of behaviour. Going back to my days of trudging around the muddy fields looking for run-away children. Sometimes I might find the child and he would return with me. Often it felt like a game of cat and mouse. This could be exciting for the child and maybe sometimes for the adult. After a few hours, he would usually return on his own accord for a warm bath and food. Simon Bain, a resident of this therapeutic community in the 1970s, commented (2012),

Although, you could say, I wasn’t a success, the funniest and indeed my fondest memories are the ‘running outs’ we used to do, with the staff spending half the night chasing us.

This raises the question of whether the need to ‘run away and be found’ can be built into daily life. For instance, hide and seek types of game or more adventurous orientation activities for older children. Hide and seek is a universally popular childhood game. Capturing why this game can be so meaningful, Winnicott (1963, p.186) said,

It is a joy to be hidden and a disaster not to be found.

The child has a simultaneous wish both to be hidden and to be found. Symbolically this may represent the child’s inner self, being hidden but also wishing to be found. Some children might feel like no-one cares enough to look for and find them. They might feel they aren’t even noticed and seen. ‘Out of sight out of mind’, as is so often the reality for traumatized children. Phillips (2009) states,

…the truant child, is experimenting: he is finding out whether the adult’s words can be trusted, whether the adult is keeping an eye on him, whether the adult’s word is his bond, whether he can withstand the adult’s punishment, or even hatred. You find out what the rules are made of by trying to break them.

In my experience, sometimes when a child ran away, being the one to go look for him could feel like a preferable activity to some of the alternatives, such as cleaning the house or attending a difficult meeting. Of course, we couldn’t easily acknowledge this, but it highlights one of the possible dynamics. As adults, what might we have invested in the child running away? Might the child be running away for the adult? Is the child running away from something that he senses going on between the adults? Thinking about what we do and feel in response to the run-away child may give us a helpful clue. Just as in the example above the adult may wish to stop the child from running away and at the same wish to join her truancy. The child psychotherapist Adam Phillips (2009) says,

The upshot of all this is that adults who look after adolescents have both to want them to behave badly, and to try and stop them; and to be able to do this the adults have to enjoy having truant minds themselves. They have to believe that truancy is good and that the rules are good. ‘The most beautiful thing in the world,’ Robert Frost wrote in his Notebooks, ‘is conflicting interests when both are good.’ Someone with a truant mind believes that conflict is the point, not the problem. The job of the truant mind is to keep conflict as alive as possible, which means that adolescents are free to be adolescent only if adults are free to be adults. The real problems turn up when one or other side is determined to resolve the conflict: when adolescents are allowed to live in a world of pure impulse, or adults need them to live in a world of incontestable law. In this sense therapy for adolescents should be about creating problems - or clarifying what they really are - and not about solving them.

This suggests that while wanting children to be safe and not truanting we also need to recognize the possible value of truanting to the child. If truanting is especially common in adolescence it suggests that it is part of a process, possibly of separation, discovery and experimentation. It is not difficult to identify with Phillips’s comment,

When you play truant you have a better time.

In one of the training sessions, I attended in those early days of my career we watched a video of the psychologist, Bruno Bettleheim (1986, Part 2, 5.58), talking about his pioneering work in the Orthogenic School in Chicago, explained that sometimes a child could not be stopped from running away so rather than ‘run after him’ they tried to ‘run with him’.

At the time, I found this an insightful way of re-framing the problem. Maybe sometimes our job wasn’t to stop a child from running away but to make the running away safe. To be alongside the child. There may be other things we can do to help improve safety. For example, if we think that a young person is likely to run away, we can make sure that he has useful phone numbers he can use if he needs help. According to Streitfeld (1990) Bettleheim could also identify with the truant mind.

Or when a child was found to be skipping school, instead of chastising him, Bettelheim admitted: "If I had the courage, I would have skipped school too. The only problem was, I wasn't brave enough. He must have a good reason for not wanting to go. I wonder what it is." The point wasn't to excuse; it was to understand.

Sometimes a child may run away on his own and other times with another child or group of children. This can raise additional worries and questions. Such as, is one or more of the children abusing another? What are they doing when they are away? Are they getting into delinquent activities? If they feel excited having adults on the run, do we make matters worse by joining in with the chase? If we don’t, are we like the neglectful parent? What happens to any children who do not join in with the running away? Is our attention on them distracted, so running away becomes a way of gaining attention? Is what we are providing in the home interesting, nurturing and stimulating so that there is a bigger pull towards staying rather than leaving?

Knowing the child’s history may also give us important clues. Is there a pattern of running away in the child’s life? Did important people in the child’s life run away? Was the family always on the move? If the child did run away before what happened afterwards? Was she punished or moved to another placement? Is running away a form of testing to see what we will do?

Running away can also be a symbolic wish to escape fears and situations. These might be connected to the past rather than a reality in the present. A traumatized child feels as if the trauma or the possibility of it is still present. Is being on the move, a way of avoiding pain? If the child had someone alongside her to hold and work with her pain would the need to run away change? If we work on facing the pain, might the need to run away get worse? Thinking about what running away may mean symbolically can be a helpful area to explore. A psychologist, Rudy Gonzalez explained a useful example to me. He had noticed in Australia that children in a care home often ran to a close-by train track. Young people and adults who have ‘behaviour problems’ are often referred to as being ‘off the rails’ or ‘on the wrong track’. Rudy refers (Barton et al., 2012, p.99) to Sharon who could often be found by the train tracks.

We could have judged Sharon’s behaviour as being only destructive, which may have resulted in a punitive response. In contrast, seeing the behaviour as an attempt to act out a positive desire which was to get on the ‘right track’ led to a more empathetic response. Through her behaviour, Sharon had introduced the symbol of the train tracks. Travel metaphors such as trains and train tracks are full of symbolic possibilities – excitement, envy for those on the train, danger, change, escape, being on the move, a new life.

I think that is a good place to finish, there is plenty to think about on this subject.

References

Anderson, S. (2012) Sherwood Anderson: Collected Stories: Winesburg, Ohio / The Triumph of the Egg / Horses and Men / Death in the Woods / Uncollected Stories, Library of America

Bain, S. (2102) Comment posted on John Whitwell: A Personal Site of Professional Interest, www.johnwhitwell.co.uk

Barton, S., Gonzalez, R. and Tomlinson, P. (2012) Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Young People: An Attachment and Trauma-informed Model for Practice, London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Bettleheim, B. (1986) Documentary Horizon

Part 1 - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IEi7QVtk-Ms&t=23s

Part 2 - https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x7n0igf

Coman, W. and Devaney, J. (2011) Reflecting on Outcomes for Looked-after Children: An Ecological Perspective, in, Child Care in Practice, vol. 17, No. 1, January 2011, 37-53, Routledge

Department for Education (2014) Statutory Guidance on Children who Run Away or go Missing from Home or Care, UK Gov: Crown Copyright

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/307867/Statutory_Guidance_-_Missing_from_care__3_.pdf

Herman, J.L. (1992) Trauma and Recovery, New York: Basic Books

Missing People (2021) Children’s Views on Being Reported Missing from Care, Missing People: Registered charity in England and Wales, and in Scotland

https://www.missingpeople.org.uk/childrens-views-on-being-reported-missing-from-care

Phillips, A. (2009) In Praise of Difficult Children, in, London Review of Books, Vol. 31 No. 3, 12th February 2009

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v31/n03/adam-phillips/in-praise-of-difficult-children

Streitfeld, S. (1990) For Bruno Bettleheim, A Place to Die, in, The Washington Post

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/04/24/for-bruno-bettelheim-a-place-to-die/5fa1f843-be85-4eae-966b-0d5abe7b8fb9/

Tuhinul Islam Khalil Interviewed in July 2013 by Ian Watson, Institute of Research for Social Science (IRISS), UK, Residential Childcare in Bangladesh. [Episode: 40]

http://irissfm.iriss.org.uk/episode/049 (no longer available)

Van der Kolk, B. (2014) The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma, Viking: New York

Winnicott, D.W. (1963) Communicating and not Communicating Leading to a Study of Certain Opposites, in Winnicott, D.W. (1990) The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment, London and New York: Karnac

Files

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting