REFLECTIVE PRACTICE: PERSPECTIVES AND SILOS - PATRICK TOMLINSON AND HELENA MOORE (2022, updated 2025)

Date added: 23/06/24

Download a Free PDF of this Article

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE: PERSPECTIVES AND SILOS

INTRODUCTION

This article is two sections taken from,

Reflective Practice: Perspectives, Silos, Resistance, and Benefits - Patrick Tomlinson and Helena Moore (2022, Revised 2025)

The focus is on how we can use reflective practice to help us broaden our view and perspective.

PERSPECTIVES, DIALOGUE, AND SUSPENDING ASSUMPTIONS

Reflective practice helps us to look at different perspectives. On our own, we can consider different ways of looking at a situation. Doing this with others has the added benefit that people in different roles have different vantage points. And we have our unique mental map, which is the filter through which we see everything.

In these two pictures of a Barbara Hepworth sculpture, we can see how a slightly different perspective can make a significant difference to what is seen. If we were to look at each image quickly, we might either see one object or two separate objects. Very different perspectives would be gained if we walked around it.

These next three pictures of another Hepworth sculpture illustrate this vividly. If we look quickly from the three perspectives and describe simply what we see, the result might seem as if we are looking at quite different objects rather than the same objects. Reflective practice helps us to get a more rounded view of a situation and to consider something from different angles. To become aware of what we cannot see on our own or from one perspective.

Referring to the work of the Physicist, David Bohm, Senge (p.225) argues that collective learning is vital to realize the potential of human intelligence,

Through dialogue people can help each other to become aware of the incoherence in each other's thoughts, and in this way the collective thought becomes more and more coherent [from the Latin cohaerere— "hanging together"].

Bohm contended that the collective view increases perception far beyond what is possible individually. A pool of shared meaning develops, which is capable of continuous development. Only by working in a group are we able to go beyond the nature of our limited thoughts, which tend to be fixed. As has been said, the definition of insanity is doing the same thing repeatedly and getting the same result, but expecting a different one. By getting different perspectives on the same subject/object, there is a fuller, more coherent, and richer view. However, this does not necessarily make the task easy. Our perspective, which seems very real to us, will be challenged. It may even challenge our sense of how we perceive reality. As Senge has pointed out, the incoherence of our thoughts is exposed.

Looking at sculptures from different perspectives may not arouse our defences too strongly. But if we are looking at our deeply held beliefs or matters where we feel vulnerable, it can feel extremely threatening. When this happens, rather than modify our views, we can become defensive and strengthen them even in the face of contradictory information. The attraction of doing the work is that we may improve our thinking, our maturity, and achieve better outcomes. To do this, dialogue must be an open and collaborative process. Referring to Bohm, Senge (p.225) outlines three basic conditions that are necessary for dialogue,

1. All participants must "suspend" their assumptions, literally to hold them "as if suspended before us".

2. All participants must regard one another as colleagues.

3. There must be a "facilitator" who "holds the context" of dialogue.

A facilitator who is outside the group may notice how the group may also become stuck and unable to observe its thinking. Groups, as well as individuals, tend to develop fixed ways of thinking. To reflect on our views and consider changing them, we must ‘suspend our assumptions’ and be willing to look at new information or perspectives. If we can do this, we move towards establishing the vital qualities of learning – a culture of inquiry and curiosity. No person or organization can genuinely learn without these qualities. We must keep learning if we are to adapt to a constantly changing and complex world at home and work. Senge (p.226) expands upon the value and challenges involved in suspending assumptions,

To "suspend" one's assumptions means to hold them, "as it were, 'hanging in front of you,' constantly accessible to questioning and observation." This does not mean throwing out our assumptions, suppressing them, or avoiding their expression. Nor, in any way, does it say that having opinions is "bad," or that we should eliminate subjectivism. Rather, it means being aware of our assumptions and holding them up for examination.

This cannot be done if we are defending our opinions. Nor, can it be done if we are unaware of our assumptions, or unaware that our views are based on assumptions, rather than incontrovertible fact. Bohm argues that once an individual "digs in his or her heels" and decides "this is the way it is," the flow of dialogue is blocked. This requires operating on the "knife edge," as Bohm puts it, because "the mind wants to keep moving away from suspending assumptions... to adopting non-negotiable and rigid opinions which we then feel compelled to defend.".

As part of suspending our assumptions, we must consider how individual and collective biases and prejudices may be a central part of our perceptions. One of our aims must be to become more aware and open to diversity and less discriminatory. Dewey (p.218) referred to the importance of an “absence of dogmatism and prejudice” and the “presence of intellectual curiosity and flexibility”. Reflective and anti-discriminatory practices fit well together.

SILOS AND INTEGRATION

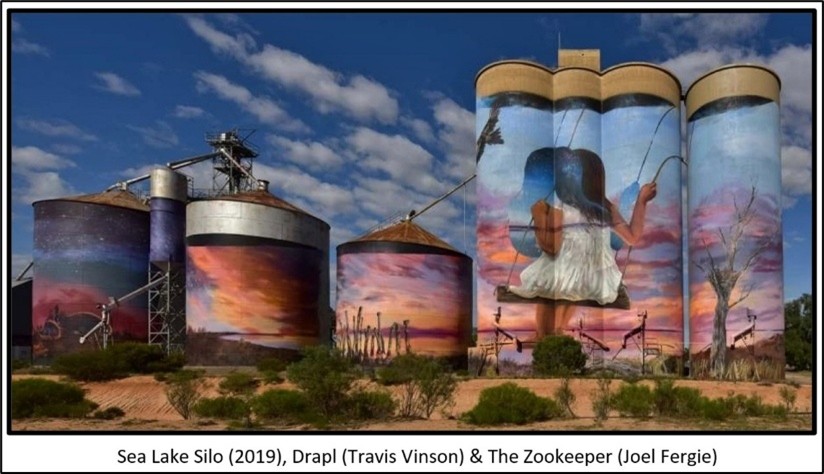

The word silo is often used in the workplace, and mostly as if being in a silo is a negative thing. Winding through Victoria, Australia, is a trail of painted grain silos called the “Silo Art Trail”. This was a creative project intended to bring rural communities together in a new way. The original silos were transformed by a group of artists who brought a fresh vision to the industrial-looking structures. The pictured silo is situated along the main highway into Northern Victoria, in a small Mallee town called Sea Lake. The painting was a community-led project and has an Aboriginal theme related to the past, present, and future. Social worker and psychotherapist, Helena Moore, lives and works in the area, and she describes some of her thoughts,

As I look at the Silos in a new way, I wonder – how are they joined up (the stairs, ramps, and chutes)? What is happening inside them (are there rooms inside)? Why are some of the silos connected? Are the small ones vital to the big ones? Are there underground parts that we can’t see? What does the painting mean to me? What might it mean to others?

Silos are an excellent metaphor. It is easy to see how the questions Helena asked herself are relevant to many situations. We might explore further with questions like,

• What are the complex and nuanced connections?

• What is hidden?

• Are there other ways to see what is happening?

• Other ways to know?

Walking Around the Silos and Cross-Silo Collaboration

As with Hepworth’s sculptures, if we were to walk around the silos, they would look different depending on our position. Some are joined together, and others are separated. Other factors affect what we see. Even if we are looking from the same place, environmental factors, such as the quality of light, will alter what we see. This is like how mood alters what we see. We can also have the same angle, the same light, and still see something different, because we each have a unique lens, like a filter over what we see. The filter is like our unique disposition, history, and cultural background.

In an organization, if silos represent different departments, teams, roles, or functions, we might question how we view the different silos. How do we reach that view? Should we be more joined-up? What is the appropriate level of togetherness or connectedness and separateness? The same applies in other relationships, for example, in a family. If our silos are part of a whole, they need to be joined up and in touch with each other. But not merged, so there is a lack of distinction between role and function. There needs to be a healthy combination of connectedness and separateness. Friedman (1999, p.14) stated how important it is for a leader to achieve the right balance,

I mean someone who can be separate while still remaining connected, and therefore can maintain a modifying, non-anxious, and sometimes challenging presence.

We could say that this is a model of integration, as the neuroscientist, Dan Siegel (2012) has said, separate but connected. Integration does not mean blended. Separation and differentiation are central to the process of becoming integrated. Differences are appreciated, but linkages are encouraged.

An integrated organization recognizes the importance of this and constantly works on it. This is a key aspect of organizational leadership. Safety, connection, and integration are the foundations of an effective organization. In the silos picture, the artwork integrates the various parts into a whole. In an organization, reflective practice can have the same effect as integrating and linking the parts together. It can help create a common language and way of thinking. As the history of reflective practice has demonstrated, it can help any person, whatever their role, become more self-aware and capable. Unfortunately, in some organizations, reflective practice only takes place in a silo and is not integrated. Not only is this a missed opportunity for the organization, but it may also strengthen the closed-silo mentality.

Edmondson, Jang, and Casciaro (2019) have written about what they call cross-silo leadership. They argue that it is difficult to take the perspective of others who have dissimilar roles and skills. However, they believe that when this happens, there are significant benefits to the organization.

As a rule, cross-functional teams give people across silos a chance to identify various kinds of expertise within their organization, map how they’re connected or disconnected, and see how the internal knowledge network can be linked to enable valuable collaboration.

They also acknowledge how difficult this is,

Though most executives recognize the importance of breaking down silos to help people collaborate across boundaries, they struggle to make it happen. That’s understandable: It is devilishly difficult.

Where Edmondson et al. talk about breaking down silos, they do not mean that silos should be dismantled. What we call silos in the workplace are created for functional reasons. For example, we need departments to gather specialists together. We are identified with our core skills. It helps our effectiveness and development to work together in a team. However, the term silo is usually used to mean a closed team or department. One that is not open to perspectives from outside the silo. What we need to strive for is the right balance between getting on with our specific tasks and being interested in what others are doing. How are the organization’s activities, teams, and departments (silos) integrated? What is the right degree of separateness and connectedness?

It is the responsibility of leadership to role model how to work across silos. Without this, it is unlikely that effective cross-silo collaboration will happen. One of the benefits is that it encourages people to ask questions and to be curious to understand the work and perspective of others. If we are more tuned in to the views and concerns of others, we may make better decisions because we are more aware of the potential consequences outside of our ‘silo’. These qualities are a key part of reflective practice and essential in effective and innovative organizations. As Edmondson et al. state,

Today the most promising innovation and business opportunities require collaboration among functions, offices, and organizations. To realize them, companies must break down silos and get people working together across boundaries.

REFERENCES

Dewey, J. (1910) How We Think, Boston, New York, Chicago: D. C. Heath & Co

https://bef632.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/dewey-how-we-think.pdf

Edmondson, A.C., Jang, S. and Casciaro, T. (2019) Cross-Silo Leadership, in, Harvard Business Review

https://hbr.org/2019/05/cross-silo-leadership

Friedman, E.H. (1999) A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, New York: Church Publishing, Inc.

Senge, P.M. (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Currency, Random House

Siegel, D. (2012) How to Successfully Build an "Integrated" Child

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h51lgvjI_Zk

Files

Please leave a comment

Next Steps - If you have a question please use the button below. If you would like to find out more

or discuss a particular requirement with Patrick, please book a free exploratory meeting

Ask a question or

Book a free meeting